…the punchline is that they’re not looking for a quest—they’re already on one.

So goes The Barkeep on the Borderlands. Conceived, and primarily penned, by W.F. Smith —joined by a veritable who’s who of indie RPG writers like Ava Islam (Errant), Marcia B. (Fantastic Medieval Campaigns), Zedeck Siew (A Thousand Thousand Islands) and Chris McDowall (Electric Bastionland) among several other— Barkeep is the 2023 ENNIE Gold winner in the Best Supplement category. And it’s a winner for very good reason. Actually, a lot of good reasons.

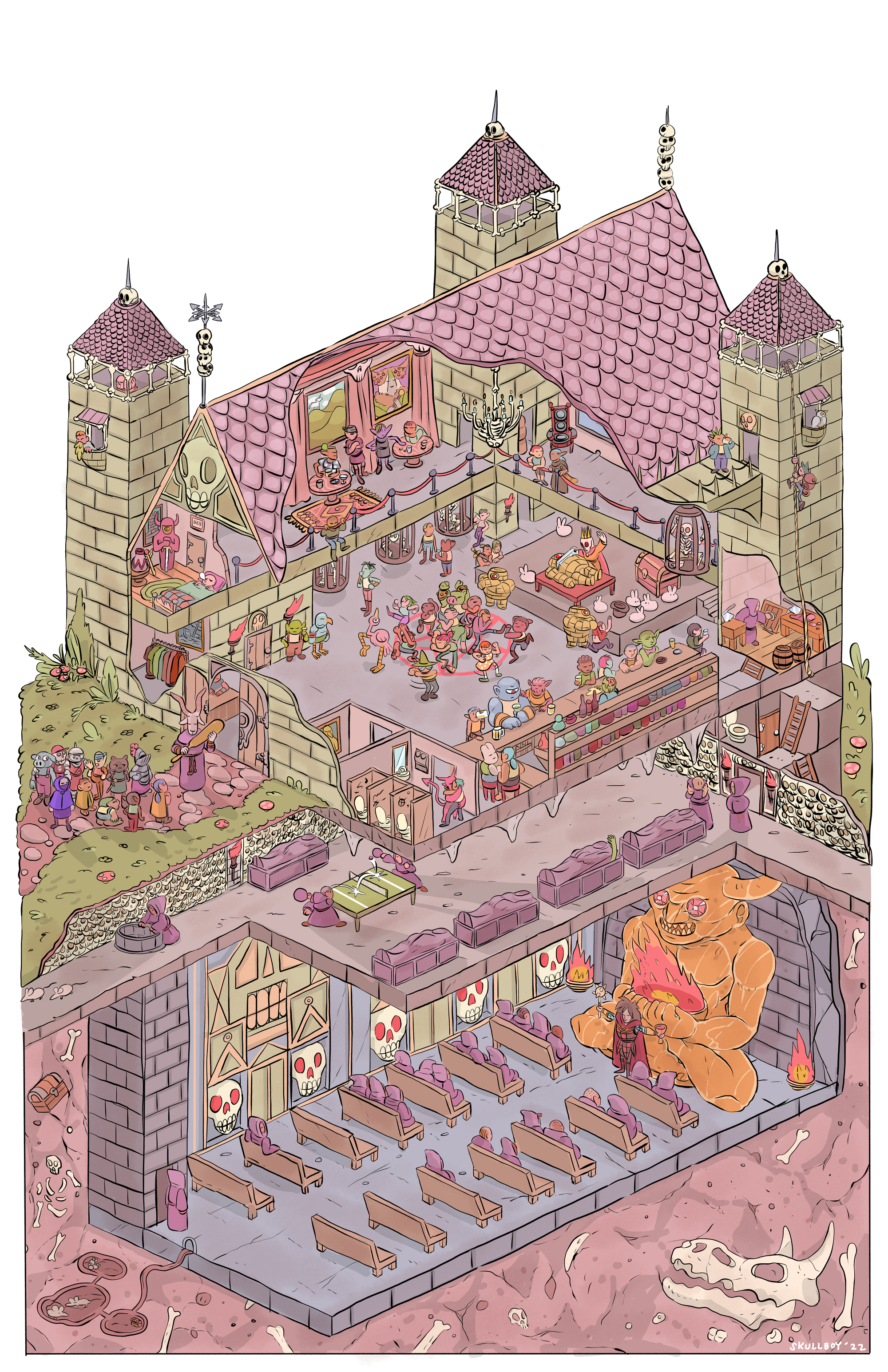

The adventure’s premise is that the Monarch has been poisoned, and they emptied the royal coffers to purchase an antidote—which never arrived. It was instead accidentally delivered to one of the setting’s many taverns. The party (the aptly named ‘jolly crew’) must find the antidote before six days are up. That’s easier said than done since the next six days are also the annual festival of the Raves of Chaos, so absolutely everybody will be out on the town.

The adventurers will have the opportunity to explore no less than twenty different taverns, each with its own unique concept and random tables of staff, regulars and signature drinks. Each bar brims with a unique character and style. For Smith’s part, many of them are based on his old haunts.

‘Almost every bar I wrote is inspired by a bar in my college town, although very loosely as there are no phoenixes in any rafters of the bars,’ Smith said. ‘Real life bars served as inspirations for even the stranger pubs like Someone’s Apartment (inspired by an eight-day-long party my friends and I threw at a friend’s apartment until the friend, and their neighbors, tired of our rambunctiousness), Quasi-Parliament (a 200-year-old debate hall that is maintained by an extemporaneous debate society and, downstairs, allegedly operates a small, secret bar [and operated as a speakeasy during Prohibition, accordingly to local lore]), and the Royal Wine Cellar (not an actual prison, just a basement bar near city hall that had iron bars on all its windows and a definite dungeon vibe).

‘The most direct inspiration was probably Our Lady of the Sacred Speakeasy, which was inspired by Sister Louisa’s Church of the Living Room and Ping Pong Emporium. I’ve played ping pong in the back room of that bar while wearing old choir robes many-a-night.’

If any particular bar strikes a GM’s fancy, they have carte blanche to lift it out and drop it into their own game. But tying them all together, as the setting for a coherent and self-contained adventure, are Barkeep’s timeline and pub-crawling procedure.

That timeline consists of a day-by-day rundown of the Raves’ events, currently circulating rumors and the location of the antidote, which gets passed around a fair bit thanks to the machinations of various NPCs. It all culminates in both the end of the Raves and of the Monarch’s life, creating a compelling ticking-clock plot device that keeps the PCs hustling around town in pursuit of their prize.

That quest is both supported and complicated by the module’s pub-crawl procedure, which measures gameplay in turns: indistinct amounts of time needed to perform actions like traveling between taverns and drinking therein. Each turn, the GM rolls a Risk Die, which indicates whether revels continue as normal, if the characters need to refresh their drinks or if a Setback occurs.

When drinking, players will roll a Sobriety Die, the workhorse of the drinking mechanics that Smith developed in reaction to pervasive homebrew 5e drinking rules. Using the latter, characters receive mounting penalties until their inebriation ultimately grants them damage reduction. Smith sees this as too proscriptive: either avoid drinking at all costs, or powergame and build a character that thrives on alcohol-induced resilience.

Barkeep’s solution is a more balanced risk-reward system. Based on their constitution (or equivalent attribute), characters are assigned a base die ranging from d8 to d12. When they roll that die and get a result of 1–3, their die downgrades one step, and they suffer some perks and detriments, both social and physical, depending on their level of inebriation. They can spend a turn drinking water, which lets them bump their die back up a step, or they can double down and and dive deeper into their cups.

Why would anyone do the latter? Because they’re in a bar during a festival, of course. Anyone who isn’t indulging will draw suspicion from other revelers and tavern keepers, and that will ultimately make their pursuit of the antidote more difficult. And even if they are drinking, the jolly crew must still contend with ambient events that can threaten to throw them off course.

Setbacks punctuate the main quest with interesting, colorful occurrences. When moving between or hanging out within taverns, the jolly crew may encounter random Sidetracks and Situations, respectively. Some of these offer opportunities to expedite or advance their quest, including connecting with important NPCs.

Some Setbacks are self-contained, while others intersect faction activities or lead the jolly crew to other taverns, tying the various setting elements together into a living, breathing whole. That’s no mean feat for a project with so many contributors.

‘Each pub went through probably 3.5 or so revisions and connections started to be added organically,’ Smith said. ‘The only hard and fast effort we made was to attempt to give each pub a sidetrack or situation to visit another pub, whether it’s receiving an invite to the Royal Wine Cellar or following non-player characters to a wedding reception at The Birdcage. Also, all of the factions appear throughout the pubs, which gives an additional sense that all the pubs are part of a larger milieu.’

Just about anyone could page through Barkeep and find something to love about it, whether that’s the premise, a location, a particular character or its many other aspects. But appreciating how well crafted it truly is, as a whole, requires one to explore its roots, both personal and cultural.

Smith began playing RPGs in college, starting with D&D 3.5 before moving on to 5e and, ultimately, into more rules-lite games like Into the Odd, and the family tree it spawned, as well as alternatives like PbtA-based systems. His preference toward rules-lite games that embrace spontaneity parallels his background in improvisational theatre.

‘In high school, I founded an improv troupe that put on a couple of shows a year,’ Smith said. ‘I also competed (to the extent that improv can be competitive) in a state-wide improv competition. We mostly did short form improv, theatresports style, but also did a few long form scenes during our performances.

‘Part of the initial draw to running tabletop games was that it was an outlet for the same creative juices that fueled my stints at improv. It is why I prefer minimal prep—I thrive off of rolling with the punches and reacting to whatever the players decide to do. This approach naturally leads to games with more player agency and, among the best groups, gives an almost writers’ room feel to each gaming session.’

Smith brings that feel to Barkeep, keeping the adventure very open to player agency and letting them find their own way through the guiding plot. Simultaneously, Smith’s ‘procedural predilections’ support the GM and help structure this more open experience. But Barkeep’s openness has origins farther back in time than just his improv days.

To really understand Barkeep’s underpinnings we need to travel back to 1979. That year saw the first appearance of Gary Gygax’s The Keep on the Borderlands, one of the most notable D&D modules of all time. Originally a standalone release, it was later included in the Basic Set, a gateway for new players to enter the game.

For many, it was their first encounter with D&D and RPGs at large. It is widely known and referenced to this day, and has been revised, reprinted, and adapted many times over. Barkeep on the Borderlands is obviously one of those adaptations, and brings its own unique twists to the table.

The original Keep is a wilderness exploration adventure written in broad strokes. It sees the PCs set out to defend the Borderland against the malicious threats dwelling therein. This will take them to the Caves of Chaos, where they’ll fight various monsters, humanoid and otherwise, and the undead and cultists dwelling in the Temple of Evil Chaos. Vanquishing them will ensure safety and prosperity for the Keep’s human inhabitants and future settlers.

But Smith doesn’t take that premise at face value. In 2021, he published a compelling counter-reading (‘The Keep on the Borderlands is Full of Lies’) on his blog, Prismatic Wasteland. He argues that the module presents a one-sided, heavily biased perspective on the scenario, one that favors the human society. Rather than being a bastion of law amidst the anarchy of the borderlands, he reads the Keep’s society as an oppressive, fascistic regime boasting a highly militarized populace who are not only empowered but eager to inflict corporal punishment for even relatively minor infractions like shoplifting.

‘I find the Keep in the original to be the more sinister location,’ Smith said. ‘It is just as deeply detailed as the dungeons (and, unlike the Caves of Chaos, is the namesake of the module) and is the base for the many villains of the module: the overzealous guards, conniving priests, and whoever tells the players that “Bree-yark” (goblin for “hey rube!” and is used by goblins to sound an alarm) means “we surrender” in the goblin language.’

On the flip side, the various groups of goblinoids, orcs and kobolds (among other denizens) are not doing much of anything. They show no signs of preparing to siege or invade the Keep. They’re mostly sitting at home with their families (the module specifically notes the number of adult males and females and children present in each location). The Chaos Raiders can easily be interpreted as a band of freedom fighters (with Smith drawing a parallel with Robin Hood and his Merry Men). And the moniker ‘Evil Chaos’ smacks of heavy-handed, pro-Keep propaganda writ in boldface.

‘I think Keep would be better if it had a ticking clock—perhaps a timeline of when the monsters of the Caves would raid the Keep like the adventure prologue claims—and if it had a bit more specificity of the motives of the denizens of the Keep and Caves,’ Smith said.

‘However, the “incompleteness” of The Keep gives part of its lasting appeal. You can project whatever you like, my reinterpretation included, on The Keep without changing a thing. I hope that Barkeep achieves a similar level of stripped-down, open endedness as Keep because, while the locations and timeline are more detailed than The Keep, it leaves ample room for player action or inaction to drastically change how the adventure is experienced each time.’

Barkeep is set 200 years after the original Keep’s conclusion. The Keep has expanded its footprint, and its leadership has changed hands from the Castellan to the Monarch. The periphery has become the centre; the goblins, kobolds, ogres and chaos cultists who previously lived in the wilderness have been integrated into society. The annual Raves of Chaos commemorate the people who helped it happen: those adventurers who crawled the Caves of Chaos two centuries ago. Much has changed. Much has also stayed the same.

‘Now, instead of a Castellan scheming to drive goblins from their homes, it is goblins plotting revenge for the atrocities committed during the original module,’ Smith said. ‘All the while, the cult of chaos grows more powerful.’

This bringing-low of law and of the powerful is the overarching premise that couches the adventure, but the motif is also at the forefront of the adventure’s contents itself. The Raves of Chaos seamlessly adapts a real-world Western tradition to the Keep’s fantasy setting: the folk culture of carnival (a Christian term whose tradition extends much farther back into history).

Traditionally, in the days before Tilt-A-Whirls and funnel cakes, carnival was an all-encompassing cultural frame that constituted a second life and a second world outside mundane life and the official order that governs it. Social hierarchy dissolved, and in many cases, a ‘lord of misrule’ was appointed to serve as a parodic figurehead of the festivities. Those revels included a generally playful atmosphere as well as spectacles and pageantry (seen today in celebrations like Mardi Gras and Carnival of Brazil), jokes and humor, and an emphasis on the body. The latter encompassed feasting (which, besides being a primordial form of human communion, marked historic ruptures in the status quo), sexuality and, of course, drinking. After all, what’s a party without some libations?

Barkeep incorporates all of these elements in the Raves of Chaos, which commemorates the ‘triumph’ of humanity over the lawless Borderlands. The Monarch’s (lawfulness’s) power recedes; ‘For one week each year the Bailiff is just a private citizen, and few laws, if any, are enforced. During the Raves of Chaos, the city watch cedes the powers and responsibilities of law enforcement entirely to the Church of Chaos.’

The first day of the Raves is the Ambush of Kobolds, which the populace celebrates with ‘tricks, traps, jokes and japes’. The second, the Orgy of the Ogres, is ‘a day to indulge in food, drink and vice until stupefied’ with ‘no end of buffets or shameless bacchanals’. On the third day, the Jubilee of Goblins, ‘everyone wears thick coats and eats a heavy meal’ in the morning before they ‘doff their coats and nibble on something light’ in the afternoon and in the evening ‘wear something skimpy and just drink’. Day four is the Parade of the Minotaur, when ‘the people of the Keep dress as monsters and parade through every street’. The fifth day, the Feast of Gnolls, is ‘a feast day, but in order to eat cooked meat, you have to win a fight’. The sixth day, the Culmination of Chaos, sees ‘the people of the Keep worship chaotic deities by drinking wine and doing things they’ll regret’.

Point for point, Barkeep incorporates every aspect of a traditional folk festival, from hierarchical dissolution to the whole spectrum of pastimes and activities. It does so in classic Keep style, by giving just enough detail to spark the imagination rather than belaboring the point. Like the characters of the taverns themselves, all of these aspects are drawn from Smith’s own experiences, giving them a greater vibrancy than probably would have been possible if they were regurgitated from detached study.

‘My sense of medieval carnival culture comes from the same place as the inspiration for the pubs themselves: my time as a student,’ Smith said. ‘As a student at a school with a robust party culture, many of our parties and events resembled, in some ways, the medieval hard-partying carnivals. The list of strange events that seemed to exist only for those with the free time that undergrads have but don’t fully appreciate included the semiannual beerlympics, the masked ball, Rubik’s cube parties, the hat debate, the all-night meeting, and—of course—the end of year steak night fight night, each with its own set of evolving traditions.

‘Key aspects of each event were the elaborate costumes and subversions (or, more accurately, inversions of authority). Take steak night fight night, for instance: it was held at the end of year the day before spring final exams began. The main event, as the name suggests, involved gathering in an abandoned clearing in the middle of the forest with a grill and libations. The participants would form a circle, in which any member might challenge another, to a fight or other lively competition. The winner would be rewarded with a freshly grilled steak. After the fights ended, a member dubbed the “chief justice” would create a bonfire where people could burn papers of their choice—perhaps class notes, love letters, or anything that they wished to rid themselves of as the school year ended. Once the sun begins to set, everyone would change into togas (of the ahistorical, bedsheet variety) and adjourn to a nearby apartment to enjoy some revelry.

‘The traditions for each of these pseudo-festival days has evolved over time in ways that none of the participants know. No one is sure who began steak night fight night or when, we only know that we do it. I took a similar attitude to the Raves of Chaos, a celebration rooted in a historical event, re- and mis-interpreted over two centuries.’

RPGs are, in many ways, a modern descendant of this folk-cultural tradition. When we play, we do so in worlds that stand fully apart from our own. We put on metaphorical masks (or, sometimes, literal ones when we cosplay), we crack jokes in and out of character, we may indulge in a drink or two (or more) at the table. We do it all for no reason other than sheer playfulness, a psychological renewal that helps us to deal with the humdrum strictures and rigors of the everyday life we must inevitably return to.

Barkeep folds the shared aspects of games and festival onto and back into themselves like well-prepared dough. It explores the historical spirit of revelry within the framework of a contemporary manifestation of that spirit. Inspired by personal experience and with thoughtful, appropriate treatment of its source material, it’s an instant classic that deserves a special place, right beside Keep, in the canon of RPG adventures.

Or maybe it’s just an excuse to drink and talk some stories with friends. You decide.

Barkeep on the Borderlands is out now and available from prismaticwasteland.com/shop

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 5 (Dec '23)