It was that sentiment which drove young Ava Islam headfirst into a book titled Dungeons & Dragons. She started role-playing with 2e loyalists, one of whom gave Ava a copy of the Mentzer red book (the B in BECMI). She convinced her father to purchase a big box set, but instead of containing the treasures she knew and loved, it confronted her instead with the D&D 4e Starter Set.

RPGs passed out of Ava’s life for years until 5e landed on her gaming table. Imagination rekindled, she unwittingly ventured into the online OSR scene, and after absorbing the ideas and play-style, she set out to implement both in 5e.

It didn’t work, and it left Ava hungry for a game that delivered the desired experience. At the time, that game —the game— was The Black Hack. Its rules-lite system, though, raised new obstacles. The almost microscopic cracks that other gamers easily stepped across appeared to Ava as unbridgeable chasms.

For example, how do parties move across hexes? What is that action’s formal basis as part of the game instead of just an utterance at the table?

Ava scoured the blogosphere, used what she found to fill in those cracks and then rebuild the emaciated infrastructure entirely. She did not intend to design (or rather, compile) a game; she just wanted to play one. But for her, it was more than a matter of entertainment.

‘[I was] broke, constantly on the verge of homelessness, dropped out of university after being the “golden child” of my middle-class immigrant family, spending every day getting high out of my mind till I could drink myself to sleep,’ Ava said. ‘The only thing really keeping me sane was running my games and writing Errant.’

Errant harkens back to fantasy adventure gaming’s roots while diverging from them and the overall trends in the genre’s almost 50-year history. Fantasy RPGs infamously labor under the mechanical bloat inherited from wargames. Errant reduces the cognitive load for all players, especially the GM, through its light rules, its comprehensive procedures, and their efficient presentation.

In its every aspect, Errant minimizes the rolls and arithmetic necessary to determine an action’s outcome. At the same time, specific aspects —narrative positioning and qualitative advantage, combat feats, arcane and divine magic and many others— provide guardrails for player creativity and agency without straitjacketing them.

The procedures —fighting an enemy, running a business, mass combat, overland travel and every other situation fantasy adventurers conceivably find themselves in— guide players through the four turn types. Initiative, exploration, travel, and downtime turns can instantly and seamlessly shift to accommodate players’ immediate goals.

None of this is novel to Errant; it self-admittedly deploys a structure as old as RPGs. Errant innovates by excavating and explicating this structure and bolstering it with streamlined procedures across the system. It empowers gamers with clear cognitive models of how play progresses at all scales, how different subsystems flow and how these components interlock and interact.

Errant’s emphasis on simplicity is the ‘rules light’ aspect of its tagline. The diversity and structural support for player goals is the ‘procedure heavy’ bit. A single procedure is mechanically light; the vast spread of procedures —from melee to mass combat, running a business, standing trial, pursuing a rivalry and beyond— is heavy in scope, but all coalesce into a robust whole artfully delivered in linear form.

‘I found the traditional organization where character creation and classes are introduced right after the core mechanics fell flat for me personally, as without an understanding of the foundation of the system it didn’t feel like players would have any framework with which to make decisions regarding character creation,’ Ava said.

‘As the book began to find its identity more solidly as a toolkit, it just made more sense. The stuff at the beginning of the book is the most essential to the system, core resolution mechanic, the turn structure, and how to adjudicate conversations, and everything continuing forward is increasingly optional - an inventory system, character classes and attendant magic systems, sub-procedures for different types of activities in each turn type.’

Throughout the text, important game terms are stylized in small caps, and other relevant terms are italicized. These direct readers and players to the combined glossary-index, which overviews core concepts, links them to related ones, and provides page numbers for further reading.

‘I cannot stress to you how much grief this passing moment of folly has brought me,’ Ava said. ‘So many hours spent fiddling in the document just cross-referencing and making sure everything that was meant to be small caps was small caps, and that things that weren’t meant to be aren’t.

‘Eventually each page was just overwhelmed by the horde of small caps terms, and the italic/small caps distinction came about as just a stopgap attempt to manage that. I remain torn about it, as I think visually it errs just too far on the side of busy, and creates a fairly strange reading flow, though it is far easier to reference at a glance.’

The book’s front and end matter include quick-reference sheets for GMs and players, further facilitating swift, engaging play.

‘The quick reference sheet was again something that I had always wanted, at least in some form, to help keep the game feeling manageable,’ Ava said. ‘A stroke of luck in terms of printing logistics left us with just enough spare pages to fill to allow us to fit them in across the pages and in the interiors of the cover.’

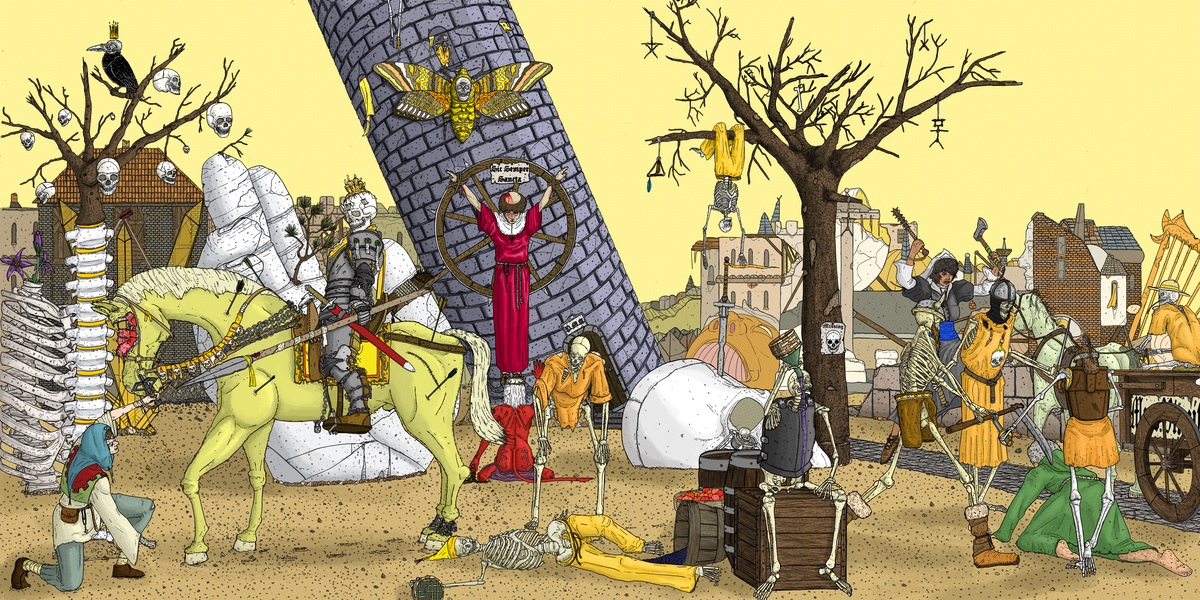

Wrapped around that cover is Ian Hagan’s artwork, a surreal and macabre wimmelbild/memento mori. Ava originally intended to use details from Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death, but Hagan’s composition fits perfectly with both the OSR’s aesthetic and Errant’s themes. Skeletons skirmish with the living; enormous faces, along with other body parts, adorn the ruined landscape and buildings; an infernal nude kneels before a trephinated priest hung on the wheel of fortune; everywhere, skulls stare back at the reader. Death (and worse) pervades the Errants’ world.

But the art goes beyond aesthetics to make a self-reflexive commentary. The front cover’s foregrounded skeleton is emblematic: it drains a tankard, pouring drink over its breastplate and down an absent throat; oblivious to its own death, it persists in activities of everyday life, just like the Errants themselves.

‘Ian Hagan’s illustration for the cover is pretty much directly after Bruegel, which is a tall order for anyone,’ Ava said, ‘but I think he knocked it out of the park with a piece that is clearly an homage but also stands on its own in terms of imagination and style. I think he captured that same sense of hopelessness and futility, but also humour and playfulness, while also adding some delightfully surrealist fantasy elements in there. I know he’s also fond of inserting authors into cover illustrations, and I suspect that the woman confronting the cart-driving skeleton is supposed to be me.’

The cover art’s duality and ambiguity persists within the book itself. There are no set ‘races’, only Ancestries that grant a small perk and carte blanche to be any creature the player likes, pushing the fiction of race into absurdity. Similarly, what would be a bestiary in any other RPG is titled ‘NPCs’, further blurring the line of personhood drawn by traditional fantasy gaming.

This reverses OD&D’s practice of categorizing anything that isn’t a party member as a monster—and therefore something that PCs can guiltlessly murder and plunder. Errant’s use of NPC seems a defiant gesture against adventure games’ roots as colonialist power fantasy, but that couldn’t be further from fact.

‘I am not really interested in subverting the colonial underpinnings of adventure games; I am far more interested in owning up to it,’ Ava said. ‘I am a colonial subject, and I have irreducibly colonial pleasures. I think it’s more interesting when we don’t front about that. In that sense I think naming them NPCs rather than monsters is perhaps a failing, a sanitization of that.’

The titular Errants, though, are anything but sanitized. They are certainly not heroes, not even decent people. The Archetypes (classes) showcase their natures in their names: the Violent (fighter), the Deviant (rogue), the Zealot (cleric), and the Occult (mage). Errant’s Alignment metric eschews moralistic (and arbitrary) pretenses of good and evil, using exclusively law and chaos, self-interested control and liberty.

The Errants begin as downtrodden outcasts who survive at society’s fringe, and things only get worse from there. They earn XP and Renown (levels) by wasting wealth and suffering material or financial losses—in addition to their mandatory lifestyle expenses.

‘The two rules that I chose most explicitly for what they’d contribute to the game on a narrative-aesthetic level were the XP for waste and the lifestyle rules,’ Ava said. ‘I really enjoyed how much they added to the picaresque feel in play, with characters always blowing through their cash and therefore in need of another job.’

Should an Errant be unlucky enough to achieve high Renown, they’ll find they’ve become the same rich, self-indulgent kingdom builder they initially despised. This character arc is inherent in traditional fantasy adventure games, but Errant deliberately underscores and then emphasizes it.

‘The only kinds of people who would become adventurers would be people [in the situation I was in], with no respectable options left. And of course those people would really just be more grist for the mill, used and spat up in service of the system they hated,’ Ava said. ‘Statistically, some of them are going to make it. And what do they do when they have made it? The same thing they were doing before: assuming the role granted to them by the system, and fulfilling its obligations. It is only the role itself that has changed.

‘This really deflates the heroic fantasy, which is based on a liberal idea of will and agency. It doesn’t matter if your adventurer is fighting for law or chaos, to avenge their homeland or retrieve a sacred relic, or whatever your special character backstory is, if the process by which they do that is always the same participation in an extractive economy. Whatever personal ideals and values you have will be subsumed by the system; the system has incentives, and incentives are what drive behaviour.’

For these reasons, leveling up amounts to throwing cash at pursuits like feasting, gaudy self-adornment, intellectual pretensions, moral elitism and any other excess a player chooses to indulge in. The procedure is called ‘Conspicuous Consumption’, a term derived from economist Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class.

‘Conspicuous consumption I think signals the sort of bathetic strain of economic humour that runs through Errant, particularly in the downtime section,’ Ava said. ‘I wanted to key my players in to the fact that the kinds of activities they should be describing here are absolutely not to be taken seriously. I suppose it also works to tie into that deflationary effect […] wherein any notion of the Errants as heroic autonomous units is contrasted against just how circumscribed they are by the socio-economic structures they exist within, and how that shapes the architecture of their agency.’

Errant, as a Frankenstein’s monster made in OD&D’s image, likewise questions player agency within the structure of the fantasy adventure RPGs that trace their lineage to the same primogeniture. For Ava, ‘knowing how to play a game’ amounts to knowing that game’s underlying procedures rather than particular rules variants. Many designers try to force novel variants without changing those procedures, attempting to create new experiences without addressing the formal basis undergirding the experience. Such uncritical praxis results in nothing new, just a more or less cumbersome set of house rules.

Neither Ava nor Errant have pretensions of doing something radically new or profoundly game changing. At the same time, Errant is also self-evidently not a reclamation of some lost heritage or golden age of roleplaying. In this sense, Errant’s inherent plot arc is a microcosm of the OSR that produced it.

‘The OSR definitely has the delusion that they’re some kind of maverick firebrand industry outsiders,’ Ava said. ‘But the OSR isn’t built on revolution, it’s built on revanchism. […] Beyond that, you’ve got people so entrenched in the dogmas and truisms spouted on blogs and forums and written in the Principia Apocrypha that the scene itself has become as entrenched and stale as mainstream trad was when the OSR turn started.

‘To be a little navel gaze-y, Errant, being my project to summarize the OSR for myself, feels like it could only be completed because the project of the OSR itself has mostly run its course. The well is dry there, all that it really is good for now is tagging as a search term on DriveThruRPG. Something is arriving to take its place, perhaps several somethings, and I’m sure they’ll all rebel against Daddy OSR as being stodgy and conservative. But as Grandpa Abe prophesied in The Simpsons, “It’ll happen to you too.”’

The OSR failed to recreate an ur-D&D, and its innovators simultaneously failed to turn D&D into not-D&D. Ingredients change to suit taste and temperament, but designers and players still follow the same recipe. Errant is a coherent and complete system, but it’s also modular; players can make substitutions to achieve their desired flavour and consistency without game-breaking knockback on other subsystems.

Ava is already tweaking encumbrance, movement in combat and other aspects as she works toward the expanded version, which she projects to be about five years away from publication. But in its current and future forms, Errant merely presents Ava’s own preferred flavour of dragon game.

‘I can’t help but feel like my predilections in terms of game design, visual design, et al. is indelibly linked to the food culture I grew up in. I have always been an inveterate dabbler and dilettante, my predilections are maximalist, and I prefer the variegated and novel over the standard and familiar,’ Ava said. ‘I have to imagine this stems from growing up in Bangladesh, where meals are judged by the quantity of dishes on the table and asses in seats. With white rice as a canvas, all the different flavours and textures of every item on the table becomes a choose your own adventure of culinary delight, to be experimented with and combined with gusto.

‘Bangladeshi eat with our hands; the word “makha” in Bengali is incredibly polysemous; in the realm of food alone it refers to any culinary techniques involving mashing, muddling, mixing, macerating, etc.; a class of dishes that are made by such a method; and the simple method of gathering and mashing together the food on your plate into a morsel to be placed in your mouth.

‘In this concept is a delight and unique appreciation for the materiality of the hand; I vividly remember how different food tasted when I was young when fed to me by my mother’s hand versus my aunt’s or my grandma’s. […] The unique way in which each individual’s physiognomy and predilections would shape and tear and break and bend the constituent components of the different ingredients together to create a bite that was wholly, uniquely theirs.

‘How some people have the best hands for one dish or another. But above all, in the absolute delight of one’s own individual hand, the irreducible joy of feeling everything from the muscles in your fingers to the oils on your skin contribute to the moment of a bite that is made just for you, by you.

‘Whenever I make Bangladeshi food at home, far too rarely, the primary joy is the tactility of feeling the rice and dhal on my fingers, squeezing lime and mashing chili into each bite, the wonderful taste of my own hand.

‘I hope for my games to be like that, and yours. To taste so delectably of one’s own hand.’

Errant is out now published by Kill Jester

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 4 (April '23)