For a man who spends his days dreaming up horrible new ways to extinguish trillions of souls Dan Abnett cuts a remarkably affable, you might say avuncular, figure. Still, the week we speak to him the British author has every right to be in fine form with his latest novel and conclusion to nearly two decades work, The End And The Death Volume III, finally published.

It’s fair to say that Warhammer 40,000 has always had something of a size fetish. Whether it’s stratosphere bursting hive cities, skyscraper-sized titans duking it out with their bus-sized chainsaws or the several mile long space cathedrals that double up as world ending battleships, this is a setting that revels in excess. Still, even by its own, often ridiculous, standards The Horus Heresy series of novels stands apart and none more so than Abnett’s capstone, itself split across three brick sized books.

Set 10,000 years in Warhammer 40,000’s past, The Horus Heresy is essentially the setting’s origin story. At the moment that humanity stands triumphant over the galaxy, the nascent Imperium of Man is riven by schism, betrayal, fratricide, attempted patricide and an entire library shelf’s worth of disembowellings, decapitations and planet killing virus bombings. Thanks to the machinations of the Chaos Gods (and one absolute bastard), humanity’s golden future is reduced to ashes and the stage set for ten thousand years of misery and the grim dark universe we’ve come to know and, strangely, love.

Starting in 2006 with Abnett’s own Horus Rising, the path to this conclusion has been a very long and incredibly winding one. Overall it’s taken more than 60 novels and over a dozen writers to inexorably lead us from the day Horus slew the Emperor to, well, an ending end and a death. Somewhat bizarrely perhaps for a sixty plus book series, it's also a conclusion that almost anyone with a passing interest in Warhammer 40,0000 has known the outcome of for well over three decades.

Abnett’s fingerprints are all over Warhammer, indeed there’s barely a corner of British sci-fi he hasn’t had his hands on at some point or another. Starting his career in the late 1980s as a junior editor at Marvel UK, one of his first writing breaks was contributing stories to the monthly Doctor Who Magazine. From there it was but a short jump to another Brit sci-fi institution 2000 AD, where he’s written, and indeed still writes, the likes of Dredd, Sinister Dexter and Rogue Trooper alongside many of his own creations, such as the acclaimed Lovecraftian neon-noir series Brink.

It’s not just the UK where he’s had an impact though. Away from our shores he’s worked on some of the biggest American comics around, including both Batman and Superman, and it was his 2008 Guardians of the Galaxy reboot that provided the template for the recent blockbuster films. It’s fair to say he knows how to work his way around another person’s IP.

Right now though it’s probably Warhammer that he’s most associated with. His debut novel, First & Only, was also the first book published by Games Workshop’s Black Library imprint back in 1999. Since then he’s shaped the setting in countless ways providing both a, vaguely, recognisably human face to the far future’s war machine with his Gaunt’s Ghosts books and exploring the thoughts, dreams and malign ambitions of otherwise unknowable godlike minds elsewhere.

So, after two decades, how does it feel to have reached the end of this particular road?

‘I can remember vividly back to 2005 when the first group of [Horus Heresy] writers were invited to Games Workshop’s headquarters,’ Abnett tells us. ‘We had no idea whether it'd be successful or if it would even last at all past the first couple of books but there was still this sense of, “oh my god, one day we will get to the end”. We didn’t know how many books it would take, but we knew it was a way off. There's actually very few times in your life where you reach an endpoint, and can look back over a significant distance, right back to the start, and go this is a complete thing.

‘So there was a very surreal sense as I worked on it that I was finally doing something that I had probably imagined, repeatedly, for years. Not that I assumed I was going to write the last book, but just getting to the end of the whole project. So yes, that was very strange indeed.

‘But it's also weird because novels are these great big, slow-moving supertanker kind of things. Writing the book took place in 2021, 2022. It took two years because it’s essentially four novels in one because I'm mad. But I finished that and sent it away with this huge sense of relief. Then over the course of 2023, there were periods where I’d get the copy edits back, so the project wasn't finished but the hard work was done. And then it's only much later when I'm well into my next thing that it comes out and everyone's going, “Oh, you must be so pleased”, and like yes but that was last year!’

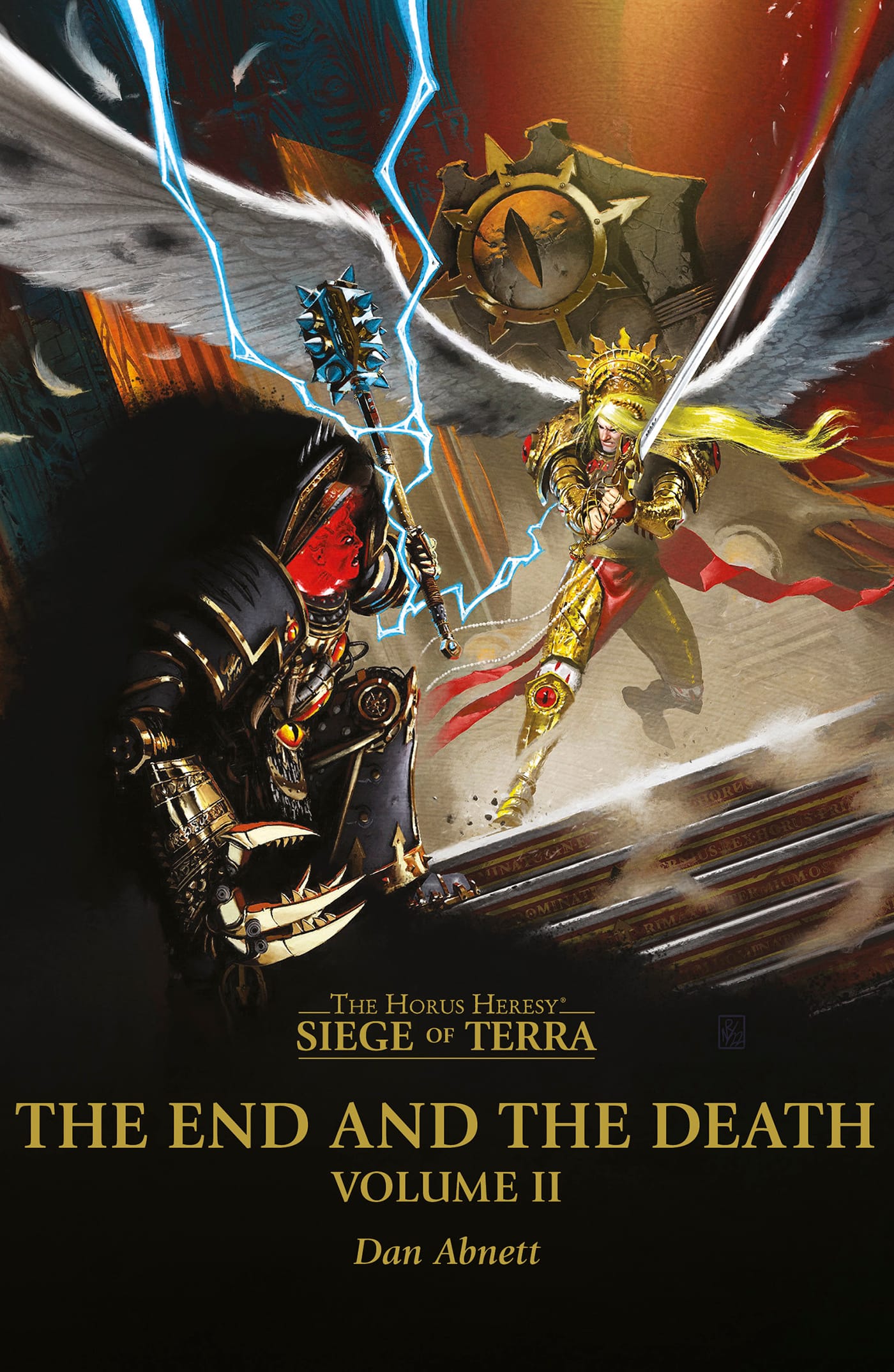

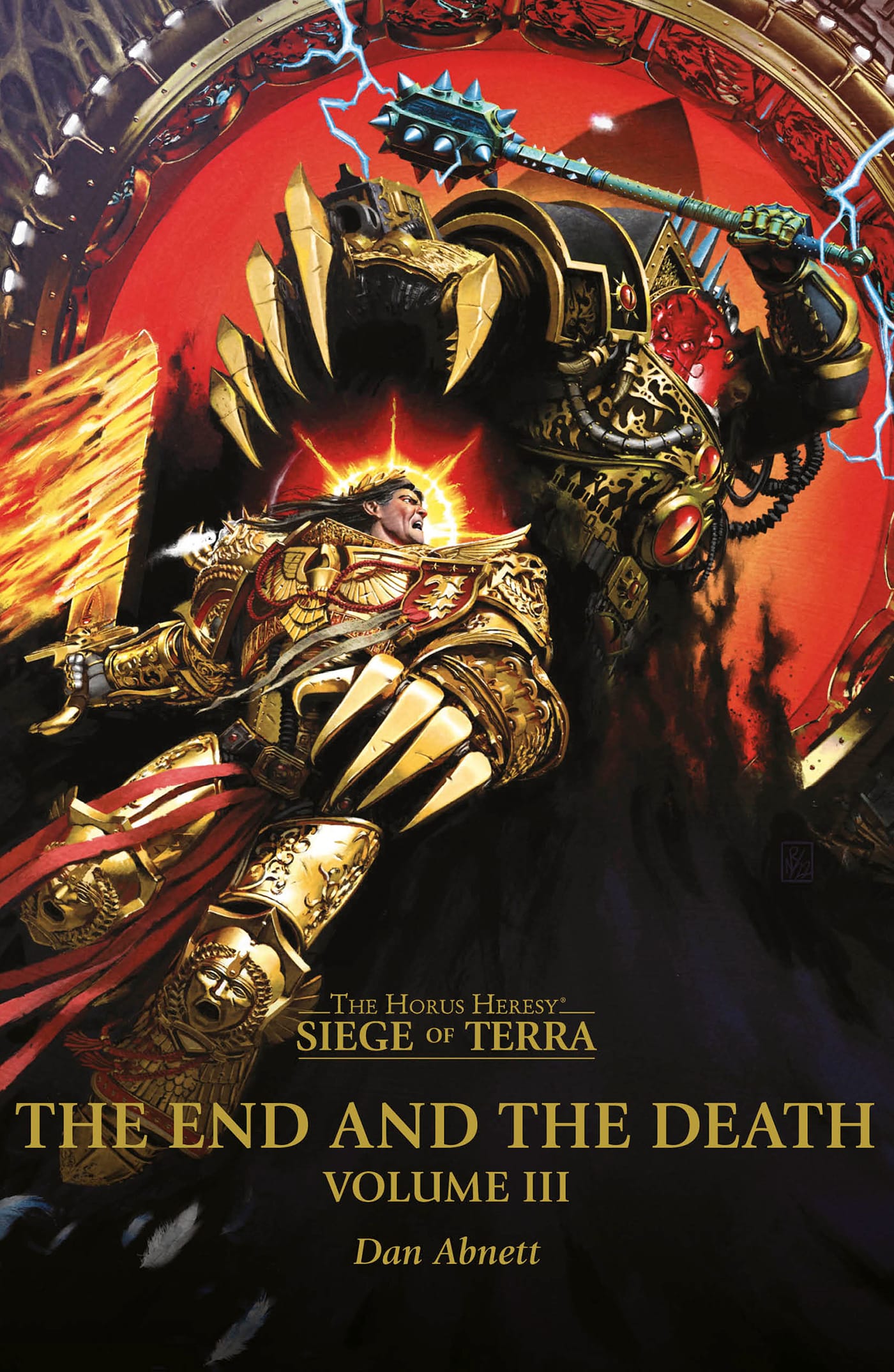

The three volume The End and The Death is indeed a supertanker, if not Super Star Destroyer, of a thing. Told not to worry about otherwise annoying things like word counts Abnett turned in a novel that was so large current book binding technology meant it had to be broken up into three, still mammoth, books. The end result is a story that spans time, dimensions and space, and features a cast of hundreds, from army grunts experiencing the worst day of their lives to demigods with the future of the galaxy in their lightning clawed hands.

‘I started writing it and I said you know the basic Warhammer, let alone Horus Heresy, is huge and operatic, well this has got to be even bigger. So I'm just gonna go for it, go all out and that means following all sorts of storylines but keeping all of those storylines equally weighted. So it's not like we spend more time with just the big characters. We need to spend as much time with the little lesser characters, because this is almost like a documentary showing you what happened on that last day.’

That last day sees the Warmaster’s flagship in orbit above a battered Terra that finally, after eight years of war, is on the edge of total defeat. With all else lost, and the forces of Chaos breaking through the walls of his palace, The Emperor of Mankind abandons his golden throne to confront his wayward son, now bloated with eldritch energies. Anyone who has read Abnett’s Gaunt’s Ghosts novels will know he can do the little people but The End and The Death presents a different challenge, what do you do when your central character has been defined for more than sixty books now as this mercurial, unknowable mystery.

‘The Emperor has been off screen essentially,’ Abnett explains. ‘So how do you tell a story where he's literally one of the main players without having him there? Which of course is impossible. So it’s devising cunning ways of having him there without having him as point of view character, or indeed anything that would completely destroy the mystery at the heart of it. He’s got to be ultimately unknowable, no matter how much you say.

‘So one of the things I did was create what might regarded as a chorus of characters in all the other storylines. Various characters who in the course of the book talk about what's going on, the world, the Emperor's plan for humanity and all this sort of stuff. They all contradict, but the idea is that they give you different versions rather than having the Emperor stand up and say this is this is the truth.

‘I’d like to think that in continuity and lore terms it's a little bit like the army that you buy at your local Games Workshop, because you end up choosing what color scheme you're going to paint it and how you're going to align them and you're using the basic raw materials and making those decisions for yourself. So it's almost like the book is an enormous box of unpainted figures and spare parts and transfers and you can then choose what the truth of that really is, even though there is some hefty nudges of suggestion.’

As for the titanic battle itself that required a different way of thinking too. Since Volume II had concluded with its own epic beat down between Horus and his angelic brother Sanguinius, Abnett knew that with Volume III he had to aim higher.

‘I realized that first of all it couldn't just be two big people hitting each other with weapons for 20 pages because that's dull,’ he explains. ‘But also we've seen that. I worked hard to get the Sanguinius fight to work because to me that was a kind of Arthurian Contest of Champions, two people testing themselves to the physical limit. But then we get to the Emperor and Horus and it's the biggest fight in the canon. So this goes back to writing comics, superhero gods in combat with each other. How do I imagine these people, who are so much more than human, fighting to the death? How will they try and outsmart each other? So we enter realms of magic and illusion, we enter realms of mythology.’

It’s to Abnett’s credit that this duel, which we return to throughout almost the entirety of Volume III and that most of us know the result of, never gets dull. Constantly switching up gears it ranges from a straight up slug fest to visceral butchery, trickery, deceit and metaphysical challenges. Chasing each other across multiple realities, the nature of the fight is constantly in flux as father and son take on different forms like some kind of power armoured Gwion and Ceridwen. They never quite make a detour to some British High Street for a quick game of Warhammer, but it’s not far off.

Something that does appear though, and plays a central role in the fight, is The Emperor’s Tarot, a staple of the setting’s often strange and contradictory occult lore. As with many of his stories, Warhammer or not, Abnett doesn't stop there though and weaves all kinds of other esoteric concepts, allusions to gnostic thought and real world magical traditions into The End And The Death. In this case those ideas are seen through the prism of Warhammer’s own internal logic, what we today think of as sorcery and magic the result of primitive mankind’s early interactions with the warp, the Warhammer material universe’s abyssal psychic twin.

Magic and mysticism are clearly things that Abnett’s both interested in and given a lot of thought to. He certainly wouldn’t be the first famous British comic writer to moonlight as a magician, so is he a dues paying, card carrying member of some secret Albionian occult tradition?

‘I do think it's a particularly British thing,’ he admits. ‘A lot of great American comic book writing does have the deeply mysterious and strange in there, but in a very sort of outward looking science-fiction sense of brave, big, bold ideas. But there is an extremely British tradition that you can trace through, let's say, Blake and Coleridge, psychogeographers like Iain Sinclair and certainly through Alan Moore, that magic is imagination and vice versa. The idea of changing the world with the force of will, which in a very literal and simple form is being able to sit down and write a book that is utterly fantastic yet completely convincing.

‘So I'm sure Alan [Moore] is genuinely a magician. But I think when he says he's a magician, he means he is a creator. He is a writer. He is an artist. Blake understood that completely. You look at Blake's work, and you think “God, there's a lot of very weird esoteric stuff going on here.” But it wasn't to him, it was the purity of expression of his belief in human imagination being the most powerful tool of all and that’s something I believe in completely. It may be a particularly British quirk, but I think that's why we're all fascinated by it. Esspecially because we live in a country, in towns and cities, that wherever you look you’ll find some weird reminder of previous thinking.’

It’s clear from both his books and speaking with him that Abnett remains a particularly good fit for Warhammer which, for all its vast global appeal, retains a deeply, peculiarly even, British sensibility. Not just in the way that it shares much of the attitude as the likes of 2000AD, gestating in the same late 70s and 80s political and subcultural environments, but in how so much of its present day revolves around sifting through the strata of its past, excavating tidbits of lore from old copies of White Dwarf or in the pages of long out of print books like Realm of Chaos.

But where does Warhammer go now? Having finally established it’s past, or at least a version of it, what about the future and Abnett’s part in it? For much of Warhammer 40,000’s life it has deliberately existed more as a setting than an actual story. A backdrop, frozen in time at one minute to midnight, for your games at home on the kitchen table to take place in.

Recently though that clock’s started ticking again, the galaxy has been split in half, demigods keep returning from the dead, everything it seems is up for grabs. Away from the Horus Heresy at least, Abnett is known for what is often called “domestic 40K”, stories that focus on life away from the frontline but another of his series, the Bequin Trilogy, may be about to take advantage of this loosening of Warhammer’s status quo, the most recent book ending on a potentially setting changing cliffhanger.

‘There is stuff in the Eisenhorn and Ravenor books where truly immense stuff happens, but it happens off in a corner of the universe that people amusingly called the Abnettverse,' he says. 'Similarly in Gaunt’s Ghosts some of the things that happened in that series are huge, but they’re but a glimmer in the distance in terms of the way the 40K works. With the Bequin books, I actually requested permission to take the story in a direction that would cross that line, and that took several years to get approval, which is why book two took so long.

‘It’s a very slow process of negotiation. It's like there's a difference between going into a Games workshop buying a copy of the game, taking it home and painting your army your way, that's writing a Gaunt’s Ghosts book, and then being led into Warhammer World, being given the keys to one of the glass cases, taking one of their priceless painted figurines and saying “I'm just taking this home with me.” That's a big difference. Now that's what they let us do with the Horus Heresy but doing that in 40k requires a much longer period of gentle negotiation, so whenever that stalls I go and fill my time by writing joyful Warhammer “shooty death kill”, and just create stuff.’

Despite our gentle attempts at persuasion Abnett remained tight lipped about the contents of the third Bequin book. Still, no matter what setting shattering revelations the true identity of that book's mysterious Yellow King might involve he isn’t turning his back on those smaller scale stories that make the 40K universe feel like so much more than just a marketing prop to sell toy soldiers.

‘One of the things that will come out from me this year is about as far from the Horus Heresy as it's possible to get it,’ he does tell us. ‘From a cast of 1000s it goes down to a cast of one in the most claustrophobic environment. I think it's still absolutely thrilling and I loved writing it and playing with that scale.

‘I think some of the most important books that will be written for 40k in the next couple of years are probably going to be the ones that see these big events, the Primarchs returning, everything like that, from a distance. Stories that treat these events almost mythologically and go, “is that really happening? I don't know, we're a bit busy over here with Tyranids.”

‘That's how you maintain that sense of that universe being so magnificently huge and above all it goes back to that unknowable mystery thing. I think for most of the time these big characters should be held at arm's length so they seem impressive. They should be frescoes on a wall, stories told around the fireside, rather than “let's have a book where we join Roboute Guilliman as he spends a day at the park.”’

On which note he’s off, chuckling to himself, though whether it’s at the thought of Primarchs in playgrounds or some horrible new way to blow up half the galaxy that will, at least for now, also have to remain a mystery.

The End And The Death Volume III is out now published By Black Library

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 6 (August '24)