One of the best things about modern board games is their ability to transport us to new worlds for the span of an hour. These worlds are distinct from the fictions that fill books or films. Rather than weaving a linear narrative, board games excel at presenting us with structures, models, the reasons behind the action as much as the action itself. To play a board game is to get a glimpse behind the curtain at the inner workings of a design, for better or for worse.

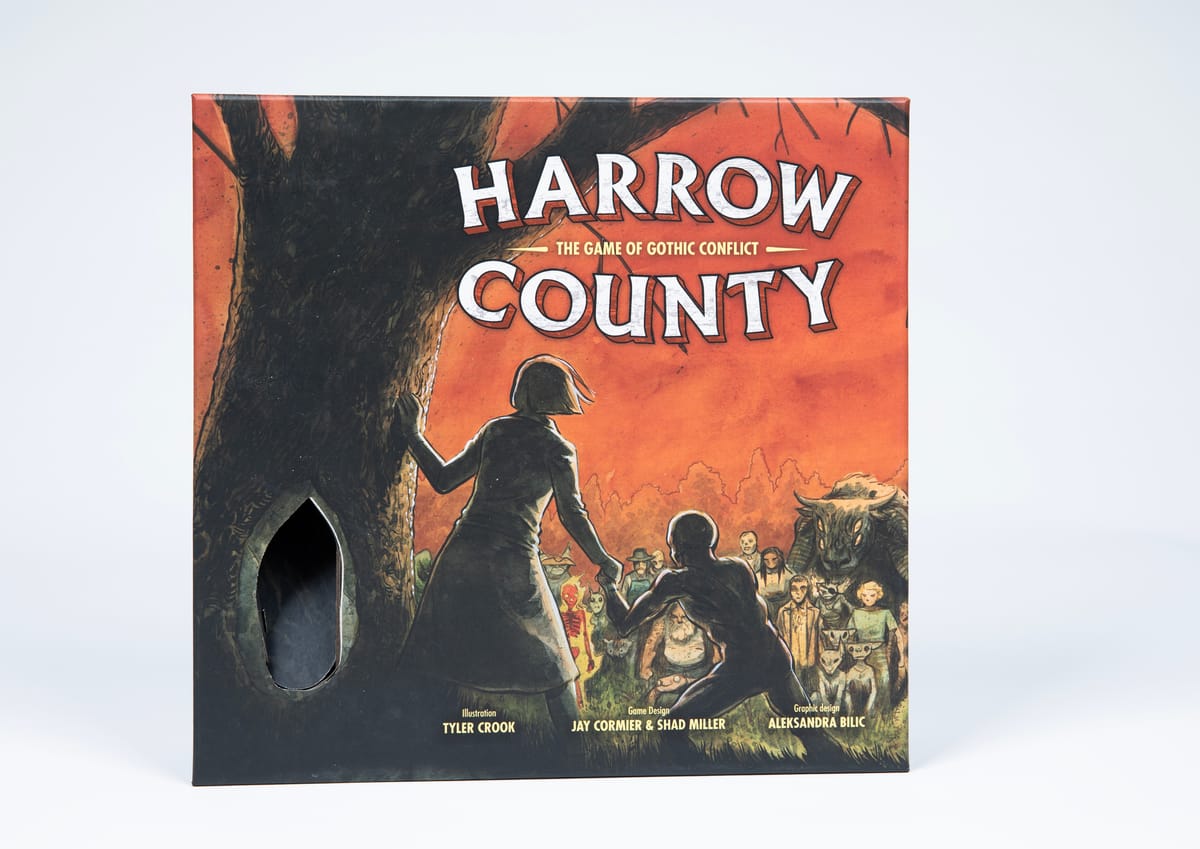

Take Harrow County. Designed by Jay Cormier and Shad Miller, and based on the comic of the same name by Cullen Bunn and artist Tyler Crook, Harrow County ostensibly repeats the comic’s tale of supernatural forces warring for control over the titular community. The comic is a regular appearance on lists of recommended horror omnibuses. Not that you would know it from the game. Rather than zeroing in on the emotional beats and character revelations that are the comic’s hallmarks, Cormier and Miller’s version focuses on the ebb and flow of each faction’s magical abilities, the makeup of their armies of “haints,” and how far anyone is from pulling off a win measured in victory points rather than decapitations.

The effect is not unlike peering behind a grimace to examine a face’s muscles and nerves — instructive, in its own way, but also likely to lose sight of the expression itself. Depending on which edition of the game you’ve stumbled upon, there are either four or five factions to consider, each with their own strengths and modes of play. The Protectors are led by Emmy, the reincarnation of a witch murdered by the locals, and these function as the game’s white hats, determined to rescue wayward villagers and bring them to safety. They’re counterpointed by the Family, a clan of jerks who spread storms across the valley in an attempt to tornado the town out of existence, and Kammi, a spoiled but powerful brat who’s hunting for the soul she once bound to a lost doll. As long as there are two other factions in play, the witch Hester Beck enters the fray to consume as many of the others as she can, not to mention take command of their haints with mind-controlling snakes. There’s also the Fair Folk expansion. We have enough on our plate without them, thanks.

Indeed, Harrow County heaps its plate too high even at the best of times. The game’s foremost weakness is its unwillingness to spell out its rules in an orderly fashion. Instead, newcomers are invited to play through successive chapters, first learning the basics and then receiving additional instruction — and complications — in subsequent plays. Early on, for instance, the Protectors are shown how to build secretive pathways through the map’s color-coded terrain hexes, using tokens, haints, and Emmy herself to shepherd those hapless townsfolk to safety. The Family, meanwhile, is more scattershot, with their own methods for resolving their abilities. With time, new concepts, factions, and approaches to victory are introduced.

Thanks to the game’s peculiar method of introducing everything, cross-referencing forgotten rules or even recalling what all you need to do at the end of each turn or round soon becomes a pain. These aches multiply once Hester is introduced, demanding three players with a deep familiarity of how those competing factions operate. That’s because Hester functions as an interloper, intruding into a conflict between two other factions to confound their plans and further her own aims.

It’s a fascinating concept. It also plops itself into an awkward no man’s land between too much and too little. A full session requires less than an hour. That’s barely enough time to get one of these factions off the ground, let alone develop an emotionally satisfying give-and-take between players. At the same time, the game is so chock-full of particulars, little rules that differ from faction to faction yet must be observed stringently lest the whole thing topple to the ground, that the rules never fade into the background. The principal emotion behind Harrow County is whiplash. Either you’re asking “That’s it?” or you’re thumbing through the rulebook to resolve one of the game’s many under-referenced statutes.

It certainly doesn’t help that there’s so much stuff to dig through. Setting up a faction requires that a player select a legend (their main character, each with a unique ability) and which of two modes their magic will operate in. When Kammi is introduced, her opponent is required to hide away her creepy doll. And that’s before we really begin setting up, with the map’s various tokens, storms, and piles of cards.

Like our dissected facial expression, Harrow County sees the underlying causes but misses their import. There are various methods for resolving basic actions: the Family pulls from a draw-bag and upgrades their tiles, Kammi pushes tokens along one of three rows, Emmy gradually powers up her abilities, and Hester jettisons the basics altogether. As mechanisms go, there’s plenty to see. But what goes missing is any sense of place, horror, or even the vaguest connection to the conflict being played out on the map. Where the comic was dark and distressing, this adaptation takes place in broad daylight. This degree of illumination is necessary for all those rules to come together, but only evokes the game’s setting via the broadest sketches.

When it comes to an adaptation, there are better options out there, including from this very same imprint. It’s only been a few years since Off the Page Games produced Mind MGMT, its version of Matt Kindt’s comic of the same name. That game was, of course, a visual treat. More than that, however, it ported the twisted uncertainty of its source material directly into the gameplay. Harrow County makes tremendous use of Crook’s blood-soaked images. If only it had given us a sense for how that blood was spilled in the first place — or why it matters.

Game Design: Jay Cormier & Shad Miller

Illustration: Tyler Crook

Published by Off The Page Games

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 6 (August '24)