The Book of Gaub is a singular object and experience. It’s both deeply personal to its creators but still accessible to any gamer or reader who might be inclined towards the esoteric and macabre. It carefully delineates its themes and tone, but its content is versatile enough to be used in any game that accommodates arcane horror and trauma. It concerns itself with the dark and terrible, but it gathers those aspects in an object that is physically beautiful without deviating from the prose’s tone.

‘It’s my most ambitious project so far,’ said Paolo Greco, the publisher and one of the creative minds behind The Book of Gaub. ‘Having recovered from a bout of a few years of crippling mental health problems I finally felt I could tackle my crowdfunding campaign for a fancy hardcover of the quality I always wanted to publish.’

The Book of Gaub is the thirteenth spellbook published by Greco’s publishing company Lost Pages and its first horror book. This grimoire resulted from Greco’s spontaneous collaboration with writers Charlie Ferguson-Avery, Evoro, The Furtive Goblin, Isaak Hill, John “Unlawful Games” Gregory, Rowan A., and Jack Shear; Ferguson-Avery and Rowan A. also contributed art alongside Enoch Duncan, Jonathan Newell, and Trevor Henderson.

‘Initially I did not know any of the writers, and treated them as an egregore of sorts,’ Greco said, referring to the occult idea of a psychic manifestation or thought-form. ‘I saw the members of the writing collective as distinct aspects of a single entity.’

Their collaboration produced 49 system-agnostic and level-less spells, each entry replete with a description of the ritual, its effects, and some evocative microfiction; 49 bits of paraphernalia tainted by Gaubian magic; 100 catastrophes resulting from the (mis)use of profane sorcery; 20 monsters; 19 adventure hooks; supplementary materials that cover rules for level-less sorcery and a table of 10 places you can find Gaub spells; and scads of monochrome illustrations and illuminations of objects, entities, and things far stranger. The tone is consistently grim and horrific, but the prose is punctuated with wry gallows humor, which keeps the mood from becoming overbearing.

The book orients all its material around the seven-fingered hand of Gaub, an image that adorns the book’s cover and recurs throughout the text and images. The hand suggests Gaub as a person (or at least a person-like entity), but the hand could also be an anthropomorphisation or a metaphor of supernatural forces, with each finger representing a distinct strain of dark magic. Greco has a background in real-world magic, which they describe (in the 1 December 2021 episode of The Lost Bay Podcast) as a technology for exercising human agency on the natural world; the hand, in this instance, emblematizes the use of suprahuman powers toward human ends.

The hand of Gaub provides plenty of fuel for fevered imaginations and nightmares alike, and this arises from the fact that, as is the case with much high-quality weird horror, it is ultimately only faintly illuminated, variously depicted, and amorphously defined — exactly as the creative team intended.

‘We do not want to explain what Gaub is,’ Greco said. ‘It’s not only a metaphor, as the Hand can actually appear in the game. It’s not only a mood, even if the horror in the book is all relatable, visceral, written after peering in the darkest recesses of ourselves, where the slimy blackness of trauma lies and festers. And it is definitely a quality: during development we framed discussions about whether something “is Gaub enough” or “could be more Gaub”. Needless to say, we made things as Gaub as possible.’

Whatever Gaub may be (or may be interpreted as), it began in informal collaboration and existed ephemerally in blogs, social media posts, and other digital spaces. Most of the book’s writing was done before Greco became involved, but thanks to their extensive experience writing spells for RPGs, they revised the prose with an eye toward maintaining consistency and reducing uncertainty about the spells’ effects since only scant formal mechanics are provided.

Making the spells system-agnostic provided an opportunity for Greco to refine each one to fit their vision for this grimoire. Whereas many games lean heavily on arithmetic and mechanics in their spell descriptions, Greco wanted Gaub’s spells to feel, to both readers and players, like real-world magic. In practice, spells produce effects, but for the caster it’s primarily experienced narratively through ritual.

‘Like a real world grimoire, the book instructs the reader in what to do,’ Greco said. ‘For example, the spells instruct the reader to “draw your sigil on the floor” rather than “the caster must draw their sigil on the floor”. This not only makes the book closer to a real grimoire, but also changes the stance of the book to make it way more personal: you can cast those horrible spells, if you want. Diegesis is a very strong tool in a black magic grimoire, as it speaks straight to the reader, and their morality. From the first page the book is clear that the central question is: how badly do you want power?’

That power is organized into seven categories; all of the spells and the paraphernalia, along with most of the monsters and many of the catastrophes, align with one of the seven fingers. The Finger Trailing Letters involves language and communication. The Finger that Points the Way affects travel, navigation, and place. The Finger on the Pulse influences the body, health, vitality, disease, and physical harm. The Finger Under the Floorboards touches on the creation, inhabitation, and distortion of space. The Finger Gnawed to the Bone deals in egress and ingress from/into the body and its inhabitation and distortion. The Finger that is Not There manipulates and erases memory and belief. The Finger Catching a Tear is primarily about evoking and affecting emotion.

Spells all invariably leverage their respective elements for decidedly malicious ends. They bear titles like ‘Occulcated Speech’, ‘Abattoire’, ‘Fractal Flensing’, ‘Cartulary Nightmare’, and ‘Panchymagogue’ to name just a few.

‘The writers browsed weird dictionaries full of desuete and half-forgotten words, and picked the best,’ Greco said. ‘This is a time-honoured practice in spell naming for RPGs, and I can say it helps! It adds a hint of forgotten knowledge that fuels the book's strong occult mood.’

But some overlap among the themes certainly exists, especially with paraphernalia, catastrophes, and monsters, which are all aspects of Gaub, and all are designed and presented for use in the reader’s system of choice. Like the spells, monsters are mechanically generic; their small stat blocks follow general OSR conventions, making them easy to implement and adapt in most games. These formal mechanics are extremely lean, though; the entries are dominated by the monsters’ descriptions, motivations, behaviors, and omens of their presence. The beasts present adversity but also advantage; each profile also includes a practical, though characteristically grim, use that players can put the monster, its body, or its remains to.

Complementing all of this printed content is a digital soundtrack comprising seven tracks, one devoted to each of the fingers. All are as darkly atmospheric and evocative as the writing and images contained in the book itself.

‘The soundtrack was done by Zoey after the book,’ Greco said. ‘I have no idea how she managed to pull it together, or how she captured the essence of each finger. It was a whole lot of work: for example the Gnawed finger involved recording her noisily eating eggs and throwing meat against walls. She also went out and hand sampled rusty gate noises from local cemeteries and took like century old interviews from asylums and put them through mixers for whispers.’

When asked about how the collective characterizations of the fingers fit together to form a cohesive whole, Greco demurred, preferring to leave that—as with all things Gaub—to the readers’ and players’ imaginations. They did, however, offer some thoughts.

“The spells are almost all pretty horrible and, while they clearly are tools to accomplish something specific, I feel sometimes revenge and pain are their only true purposes”

‘I can only offer my personal opinion, without any authority: each of the Fingers is tied to specific trauma and anxiety, and each writer contributed some,’ Greco said. ‘The spells are almost all pretty horrible and, while they clearly are tools to accomplish something specific, I feel sometimes revenge and pain are their only true purposes.’

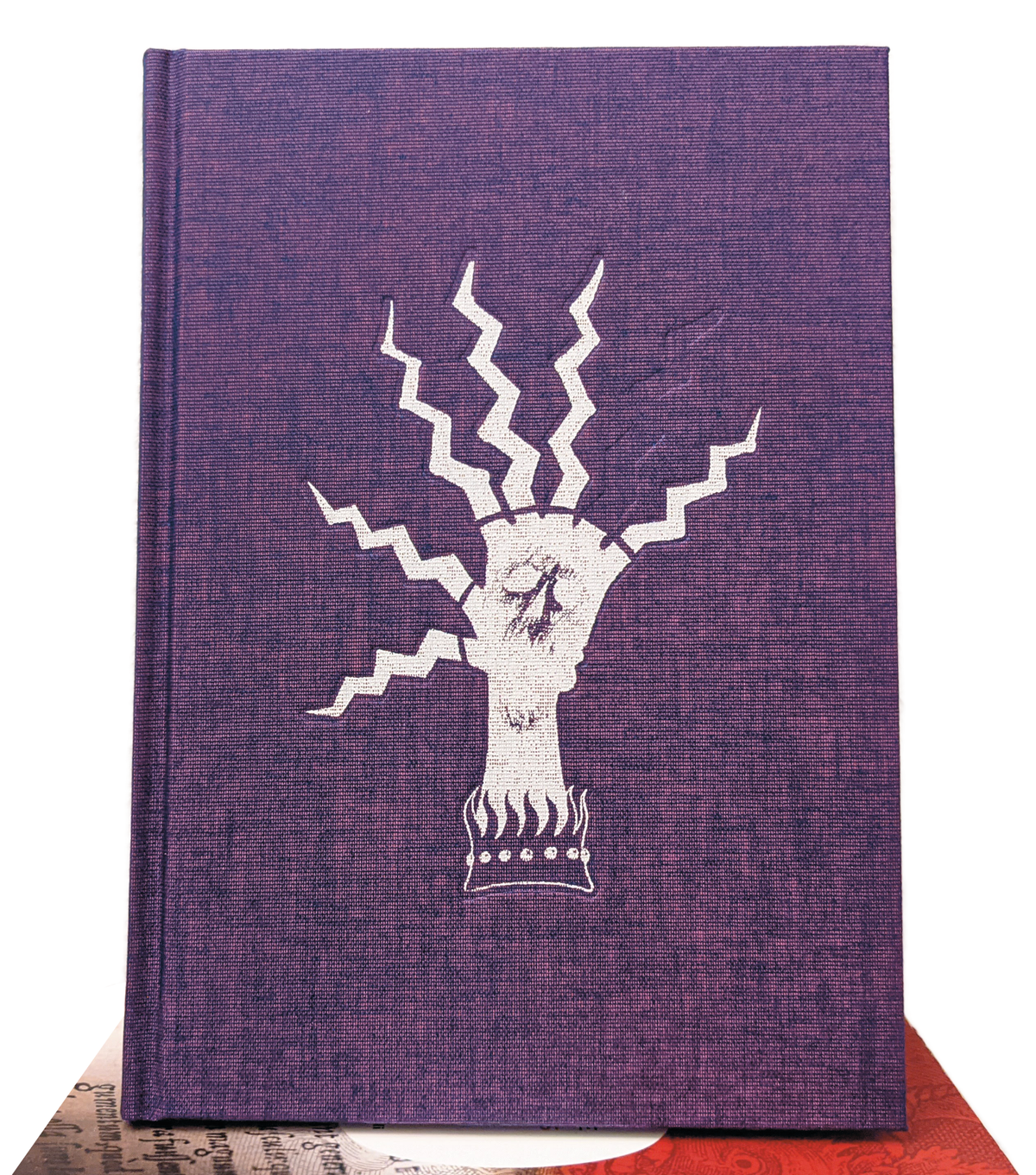

Needless to say, the creative team deftly brings the Gaub to the table, and Greco certainly didn’t skimp on the book. In print, The Book of Gaub is more than just a physical vehicle for delivering its gameable content; it’s an A5-size work of art.

The standard edition is bound in cloth that shifts from purple to blue depending on the viewer’s orientation. I’ve personally had moments when I’ve left the book sitting out on the table, caught a glimpse of it out of the corner of my eye, and asked myself, ‘What the hell is that? I don’t own any books that color.’ It’s an uncanny experience that is frankly very Gaub.

Of course, the book’s cover readily reveals its identity thanks to the seven-fingered hand with a screaming skull superimposed on the palm. The design incorporates two distinctly human characteristics—the hand and the face—in a defamiliarised and twisted presentation. The image is both silk-screened and debossed into the cover; the Finger that is Not There isn’t printed, but its form is debossed, cleverly preserving its presence-in-absence.

The wonders of Gaub certainly don’t end at its exterior. The Doves Type and IM Fell faces on thick ivory paper look, and feel, rich and refined. But Greco did more than just arrange words on paper according to standard conventions and practices: the book’s main body text is arranged in a single column whilst entries’ headings and subheadings are presented in the top and outside of the margins, respectively.

Greco’s approach and work are directly inspired by T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, the artist, bookbinder and publisher best known for his work at Doves Press and for coining the name of the Arts and Craft Movement within the decorative and fine arts.

The Book of Gaub’s primary Roman typeface is a recreation of the one whose development Cobden-Sanderson oversaw for his press, and Greco also adopted Cobden-Sanderson’s approach to applying that typeface to the page in an artistic, elegant fashion.

‘I tackle layout half as a purely geometrical composition, pursuing beauty, going for balance or dynamism or whatever else the content requires, and half as a user interface, pursuing ease of use, going for better learning or ease of browsing or whatever else the user requires,’ Greco said. ‘The user interface work is quite standard interaction design, while the composition is merely “take your glasses off and look at the elements on the page as shapes, and make it pretty”.’

One of the most striking features is the silhouettes of the fingers framing the page numbers. Within each major section—spells, paraphernalia, etc.—the relevant finger is printed darker than the others (with the Finger that is Not There appearing when appropriate) to aid in quick navigation and reference. Complementing this visual marker, the book includes a general table of contents with a categorized spell list, an alphabetized spell index and a general index of spells and monsters.

The end result is a book that is quite useable at the table, and it will compel you to use it. It will also compel you to read just one more entry even though it’s already past midnight—the worst possible time to be pondering profane artifacts, hideous beasts, and other manifestations of Gaub. And you’ll certainly to feel the urge to leave it on your coffee table so you can share its bespoke craft and unspeakable horrors with all your friends and houseguests.

The Book of Gaub is written and organized in way that’s easy to read piecemeal, but it’s concise enough that, if you’re feeling particularly masochistic, you could read it from start to finish in just a few hours. But the art, prose, and playable content are deep and inspired enough to be re-read and contemplated for much, much longer than that.

Just make sure you do so with the lights on. And don’t worry—that cobweb in the corner of the room is probably just a cobweb.

Probably.

The Book of Gaub is out now and is available from lostpages.co.uk

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 3 (Oct '22)