Many horror, and horror-adjacent, games feature mechanics that track a character’s mental state. Over the last forty years, these mechanics have changed and been refined, moving away from more dated conceptions of insanity and simpler mechanics into more nuanced, complex and thematic examinations of mental health and what it means to lose it.

The loss of sanity is the subversion of the power fantasy inherent in most roleplaying games, replacing a character’s customary progression with a downward spiral. It is, in part, a solution to the intrinsic problem of all horror RPGs; the medium is defined by choice, freedom and power whereas horror is about the loss of choice, freedom and power. The heroes in horror stories are usually unsung, their victories, if they win at all, often pyrrhic, fleeting or inconsequential. For those lucky enough to find any meaning or heroism in what they do, they must give of themselves for others. They die in the dark so that others may live in the light.

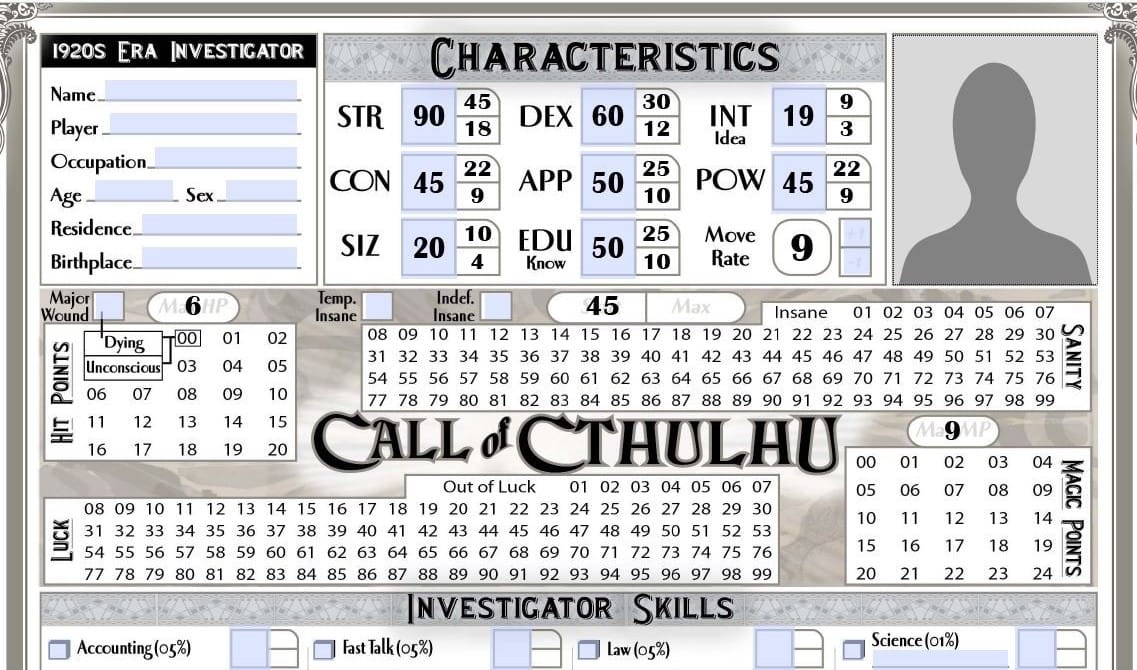

Any discussion of sanity mechanics must begin with Call of Cthulhu. Based upon the fictional universe created by H. P. Lovecraft, the ur-example of cosmic horror, the game’s sanity mechanic reflects the deteriorating mental state of Lovecraftian protagonists. Characters start with a set sanity value and lose it, point by point, as they encounter horrors beyond mortal imagining.

The enemies in Call of Cthulhu often cannot be meaningly fought and even when they are defeated this seldom matters; what is dead can never die and the stars will soon be right. In addition, the monsters you face aren’t dangerous simply because they might kill you. Each and every one is physical evidence that everything you know is wrong, they are unreality given form. The universe is infinitely more strange and cruel than you ever imagined and you are nothing. In Call of Cthulhu and its derivatives, improving their understanding of the occult often reduces a character’s maximum possible sanity rating and reading books with these truths can drive them mad.

While most editions do have some ways to restore lost sanity, these are generally small; this is a game about losing your mind and, in many ways, it treats sanity as a secondary health pool. Losing too many points at once generally triggers a panic response. As sanity points dwindle, characters may start to “go mad”. Players are encouraged to portray real mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and, should a character’s sanity ever hit zero, the character is no longer playable. They are irrevocably insane.

Unfortunately, this system is largely built on outdated concepts of mental health and feeds into stereotypes about neurodivergent people being dangerous, out of control or otherwise disconnected from reality. In addition, this game and many others impose conditions real, debunked and/or misunderstood upon the characters. Game mechanics that randomly give characters mental illnesses, or that push players into depicting neurodivergence they may have no experience of, can too easily lead to a shallow or derogatory portrayal, or one that undermines the intended tone through bathos.

It can be argued that the Lovecraftian protagonist is not simply going insane. Instead they are gaining insight into the true nature of reality, perceiving and experiencing real things others cannot. This is the model used by Cthulhu Dark and while the distinction may seem subtle, it is, if anything, more true to the cosmic horror genre.

An optional rule in more recent editions of Call of Cthulhu gives those with low sanity values moments of insight into the horrible truth of the universe. This is a direction ripe for further exploration in tabletop RPGs. One of the best examples of this is the video game Bloodborne; when characters reach sufficient insight, enemies change appearances, use new attacks and some creatures, previously invisible, can at last be perceived.

While sanity mechanics began with cosmic horror, it is not their only place within RPGs; in many ways personal horror games are an even better fit to explore those themes. In most World of Darkness games characters are no longer human and gradually devolve into some flavour of monster. While usually not directly analogous to sanity, there is often considerable overlap. The titular bloodsuckers in Vampire: The Masquerade had to watch their Humanity, but even human beings could become (less literal) monsters in the World of Darkness setting as they slid down some form of morality track, picking up troubling behaviours and literal psychological disorders on the way.

It is difficult to discuss sanity mechanics and Vampire: The Masquerade without mentioning the Malkavian Clan. The clan’s unique gimmick is a prophetic insight that is, to an outside observer, indistinguishable from madness. It manifests differently in each, often bearing a resemblance to real neurodivergence, such as sociopathy or borderline personality disorder.

Malkavians occupy the societal role of seers and jesters, known for their pranks. Well-written Malkavians often make the most compelling characters in the Masquerade setting. They have also, inevitably, been the worst. Too many players approach the clan’s unique curse and propensity towards satire through wacky, random antics or lurid excess, taking refuge in audacity. Too often the Malkavian – and by extension mental health – is a joke or grounded in stereotypes.

With morality and sanity bundled together in Vampire and most of its spinoffs, immoral acts lead to mental illness, which is an unfortunate, unrealistic implication and an uninspired way to model a character growing increasingly divorced from their human self. Newer editions have moved away from this by removing or reworking these mechanics entirely. In the Chronicles of Darkness, Morality was replaced by Integrity, which is lost through traumatic events rather than immoral acts, and instead of gaining permanent ‘derangements’ – a dated term – characters acquire Conditions. None of these are named for real diagnoses and can be removed by meeting particular criteria or after a period of time. Vampire: The Requiem’s most recent edition has Humanity loss impose similar temporary conditions as well as mechanical penalties entirely divorced from mental health.

Requiem also introduced touchstones, significant relationships that help to shield characters from Humanity loss. Often speaking to a touchstone is what resolves a negative condition. This system, in addition to being a, somewhat, realistic take on support systems, grounds a character in the setting and gives players something more than a number on a tracker to lose if their character’s Humanity plummets. This system has been used by other games since, including the Call of Cthulhu offshoot Delta Green, a Lovecraftian conspiracy thriller.

While a pure sanity system is usually reserved for horror games, plenty of games that straddle genres or dip a toe into horror – for example Eclipse Phase, Red Markets, Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play and Dark Heresy – include sanity tracks and similar systems. Generally these are less severe than the examples above, with more ways to mitigate, prevent and recover from sanity damage, or they model something subtly different such as corruption from dark supernatural forces more diabolical than the distant, uncaring horror of Lovecraft. It’s often an inelegant system, with sanity mechanics an extra burden for characters rather than the thematic or mechanical heart of the game, though there are certainly exceptions. The One Ring, set in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, uses a corruption mechanic that hews closely to the nature of evil in the source material.

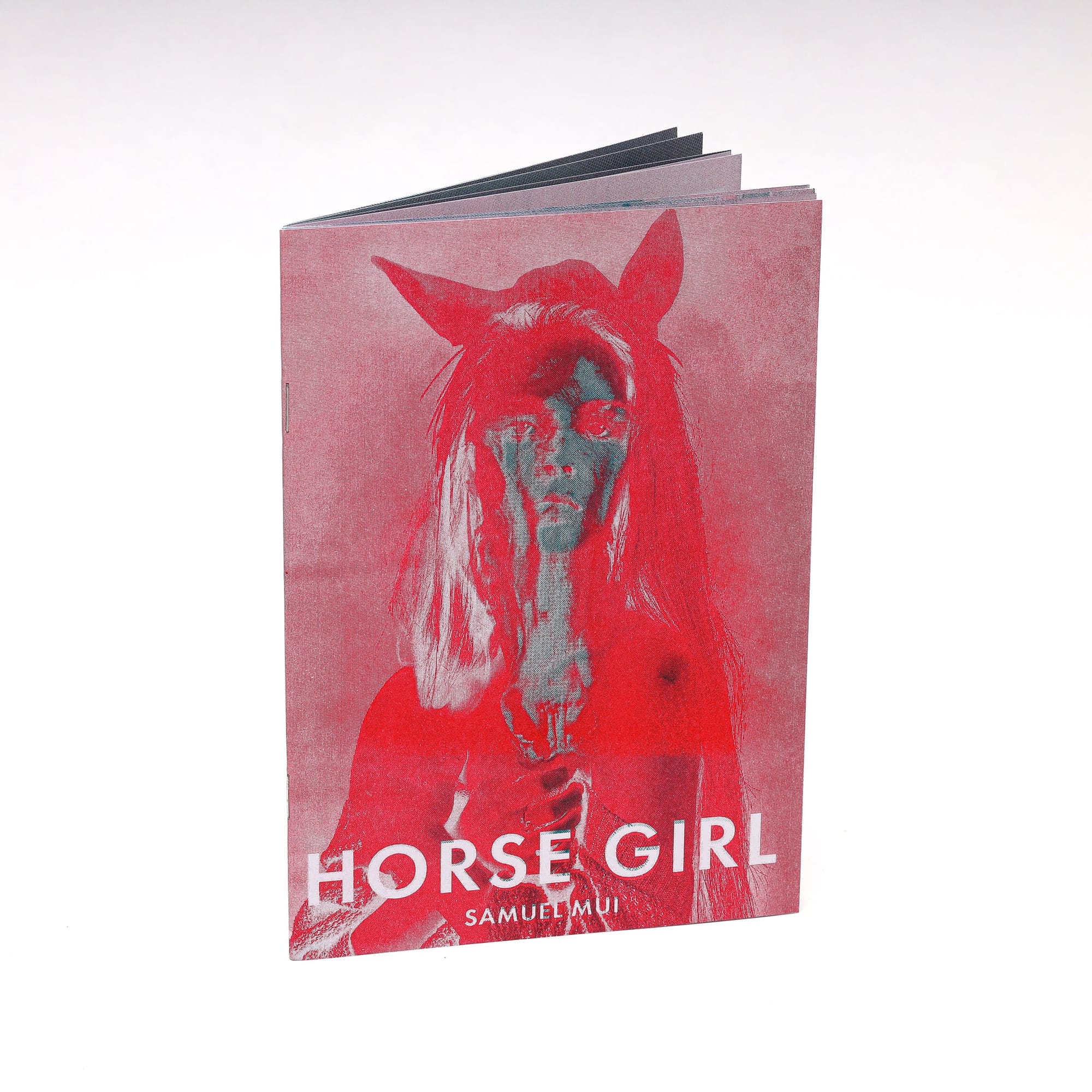

There are, however, games where declining mental health is the central point, not an accidental byproduct, genre convention or a way to model helplessness. One of the most powerful, and viscerally disturbing, is Horse Girl. In this solo journalling RPG – “dedicated to all those who have had their lives irreparably ruined by the choices they made while under sound mind” – players portray a lovesick woman whose controlling partner intends to transform them surgically and mentally into a horse. The game’s sanity track is fully externalised in the form of a tower of wooden blocks, the player removing pieces as they explore the game’s disturbing prompts. They surrender to the transformation if the tower falls. It is a profound experience, not to be undertaken lightly, and plumbs depths of uncomfortable detail that perhaps only a solo game could allow. It would be difficult to explore a game quite so dark as this with someone else, navigating your shared comfort level, and by playing alone you mirror the reality of the titular character. There is nobody there to help her, warn her or pull her back from the brink.

In Changeling: the Lost, another game in the World of Darkness series, players take on the role of human beings abducted by fae, spirited away to another dimension where they were enslaved and magically transformed. One might have served as a living candle, another may have been a literal ornament and now resembles a marble statue. All playable characters have since escaped back to the human world, their bodies and minds forever changed by the experience.This game’s sanity track – Clarity – measures both the literal mental health of the changeling and their ability to differentiate between the magical and mundane worlds they are stuck between. While Changeling is not solely about mental health – characters will face supernatural threats, navigate politics, and face the push and pull of the mortal and fae sides of their nature – it is a keystone of the game.

In Changeling’s first edition, characters gradually lost Clarity in a system modeled on the Humanity mechanics of Vampire. Though less severe and more reversible than Vampire’s ruleset, it shared many of its shortcomings. In the game’s second edition, a player’s Clarity is a health track almost identical to their physical health. Characters can slide into a comatose dream or die if their psyche is injured enough. It is possible to heal Clarity damage through a variety of means, particularly by spending time with the people and places that matter to the character (as with Requiem’s touchstones). This speaks to the more hopeful themes at the heart of the game and is a more respectful and realistic portrayal of what people with poor mental health can do to improve it. Unlike the slow but inevitable degeneration of a vampire or a Lovecraftian protagonist, a changeling can live and thrive. While they will always carry the physical and mental scars of their durance, they can and will recover and find definition elsewhere, for who they choose to be and not what they were made to be. Changelings are not framed as victims, but as survivors.

One of the more complicated and nuanced takes on sanity mechanics can be found in Unknown Armies. Instead of one sanity track, characters have five ‘shock gauges’; Self, Isolation, Helplessness, Unnatural and Violence. When characters encounter traumatic circumstances that fall under one of these categories – for example being imprisoned for Isolation, or talking to a corpse for Unnatural – they roll a stress check and mark either a failed or hardened notch depending on success or failure.

Hardened notches gradually make a character immune to that particular shock. This is not without its downsides, however, as characters are desensitised and if a character has enough hardened notches they accrue mechanical penalties. In the first edition they were described as sociopaths. Second edition changed the terminology, as sociopathy isn’t something a person can acquire. Accruing multiple failed notches can cause a character to manifest mental illness, terminology which survived the transition to second edition.

The second edition keyed the five shock gauges to ten new core skills, with a character’s ‘open’ and crossed off notches providing bonuses to a specific skill. Someone with little-to-no experience of violence may find connecting with people easier while someone accustomed to it is better in combat situations. The system encourages players to think about how their experiences have shaped the character in a way the more abstracted points systems of most other games do not. The same mechanics that punish can also empower a character. A hardened character can laugh off something terrifying; they’ve seen worse. The fact that violence is listed as a potential cause of trauma is another thing that sets the game apart from most RPGs, which revel in action with entire chapters full of special attacks and abilities. Unknown Armies famously prefixes its combat rules with a list of ways to deescalate and avoid a fight.

Unknown Armies may use the language of insanity but in truth the system is modeling something different. This is not an inescapable descent into inhumanity, supernatural corruption or opening oneself up to a wider, more terrifying cosmos. It’s trauma. Some people become desensitised when exposed to enough, others flinch at every slammed door. It’s no accident that, instead of sociopathy, Unknown Armies’ second edition labels a hardened person Burned Out.

In this, Unknown Armies was a forerunner for the shift from sanity mechanics to stress mechanics, which are becoming more and more prevalent both within and outside the horror genre. They’re far more accessible – you may not have had your mind broken by an eldritch creature from beyond the stars but you’ve probably felt worn out and overextended – and less likely to unintentionally replicate harmful stereotypes and prejudices.

In Blades in the Dark, the stress track is arguably the central mechanic. Player characters – criminals and scoundrels – take stress to push themselves, to trigger flashbacks and perform incredible feats while on the job as well as indulge in vices to reduce their stress level between missions. It’s an engaging gameplay loop and if players fill their stress bar, which is usually in their hands, they receive a Trauma. The downward spiral is far from inevitable, and much more easily mitigated by players, but it’s there for those willing to push their luck. The given traumas are vague – Ruthless, Cold, Haunted – rather than modeled on specific diagnoses. The rulebook also notes that the degree of their impact is down to the player. By roleplaying them a player can earn extra experience but there is no punishment for ignoring them. Once they have four Traumas a character is retired, with the circumstances up to the player. It’s far more likely the character will literally retire or go to prison than an asylum.

While Lovecraftian games seem unlikely to lose their laundry lists of disorders and spiraling insanity anytime soon, they are nonetheless innovating and iterating. Trail of Cthulhu has different modes of play for more gritty or pulpier rules, which alter the severity of its sanity mechanics, baked into the rules. The most recent editions of Unknown Armies and Call of Cthulhu removed many specified mental illnesses and neurodivergence in favour of nonspecific compulsions, phobias and delusions. Many games introduced bonds that mechanically encourage players to think about their character’s support network and provide a touch of realism and stakes to their struggle with demons both literal and figurative.

40 years on from Call of Cthulhu introducing SAN points to our character sheets more and more systems are diversifying in terms of what they model and how – whether it’s sanity, stress or supernatural corruption - and in recent years there has been an intentional move away from ableist tropes and simple mechanics in favour of more nuanced systems that better complement core themes and treat mental health both a little more realistically and respectfully.

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 3 (Oct '22)