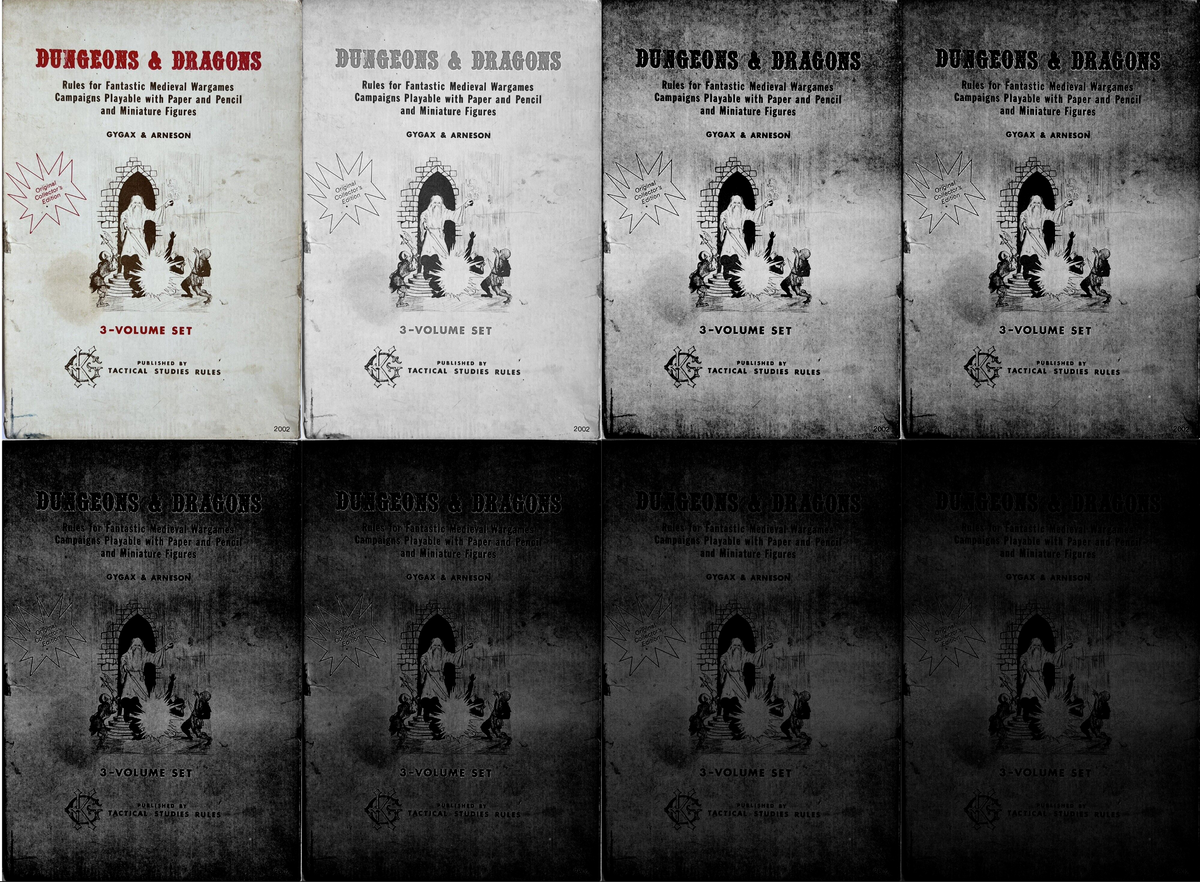

The year is 1974. You hold in your hands three small booklets titled Dungeons & Dragons: Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencils and Miniature Figures. Maybe you’re a wargamer. Maybe you’re a sci-fi/fantasy fan. Either way, when you sit down to play this game, you’ll become part of a creative vanguard that will forever change tabletop gaming.

The original D&D didn’t call itself an RPG, because its creators, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, did not realize they’d created one (so to speak). Wargames generally situated the player as a leader or a commander, though some (such as Fight in the Skies and Western Gunfight) encouraged them to play “in character” as an individual. That fundamentally shifted player priority from taking competitively advantageous actions to doing what the character’s personality dictated.

Though OD&D wasn’t the first game to situate players as roleplayers, it cleared the ground for the concept of a dedicated roleplaying game to take root, particularly in the fertile soil of cooperative storytelling that existed within the SFF fandom. These early adopters were not unfamiliar with organized activities that shared a similar, top-down structure with wargaming; some collaborative storytelling endeavors conducted by post followed defined rulesets and were arbitrated by what we’d think of as gamesmasters.

OD&D appealed to these two groups for different reasons. There was, of course, some overlap—Gygax had banked on that—but the game’s draw wasn’t restricted to the center of the Venn diagram. The potential to play it as a wargame or to use it as a tool for fantasy storytelling cast a wide net over its target demographics.

The game’s versatility stems from its incompleteness; OD&D is not a system in the modern sense, but a collection of tools to be used, or ignored. For Gygax (at least ostensibly), this incompleteness wasn’t a design flaw—it was a vital feature for an organic, heterogenous experience. ‘If the time ever comes when players agree on how the game should be played, D&D will have become staid and boring indeed,’ he wrote in Alarums & Excursions issue 2 (and quoted in Jon Peterson’s The Elusive Shift).

Whether you wanted to modify D&D to perform as a crunchy wargame or as a looser storytelling device, if you were willing to put in the work, then you could make it work for you. The original D&D isn’t a catered meal; it’s a potluck. The game exists as whatever you bring to the table.

This D&D experience is likely foreign to many (if not most) modern players. Even in our current homebrew culture, GMs typically don’t fill in the gaps from scratch, whether modifying existing rules or importing subsystems. And the proliferation of so-called retroclones has in recent decades sanded down OD&D’s rough patches and painted over them with modern expectations and conventions, effectively hiding the game’s original nature from both the uninitiated and veterans alike.

But that age of obfuscation has ended. Marcia B.’s Fantastic Medieval Campaigns revives the content of those original three booklets along with the Chainmail system (a fantasy-medieval wargaming system co-created by Gygax and upon which OD&D was predicated) and a handful of optional rules selectively drawn from across the breadth of the game’s history. Everything has been reorganized for usability and accessibility, and rewritten to avoid contravening copyright—but without “fixing” the inconsistencies and incompleteness that were the foundation for OD&D’s original success.

‘I think that although we, myself included, describe OD&D as incomplete with respect to our modern expectations, it's important to remember that not only were there no such expectations of completeness at the time when it was written, but that it was written under entirely different expectations,’ said Marcia. ‘OD&D is not a rulebook or a manual or a system: it’s someone’s framework or toolkit for a wargame campaign of their own making, which someone else may use as they see fit for their own campaign. The strength I see in this is in its amateurism, in the direct relationship the authors had to their hobby, prior to it becoming increasingly caught up in the market’s demands for a solid, reliable product.’

Fantastic Medieval Campaigns seeks to deliver OD&D to a new generation in as undamaged a form as possible. Plenty of games have adapted various older editions and iterations of D&D, but they update certain textual and mechanical aspects to align with modern sensibilities, which deviates from the reality of the original.

‘I think most retroclones of OD&D, with how they have reorganized the text to reflect modern conventions of rulebooks, have inserted modern play notions (relative to the original) in doing so,’ Marcia said. ‘This was an outcome I was trying hard to avoid, and it seemed like it worked with how many people questioned me and misremembered the original being more like what they expected than it really was.’

But this important historical and critical tool has inauspicious origins. What became Fantastic Medieval Campaigns started out as a personal experiment in the interaction between content and graphic design.

‘The original booklets were just ugly and hard to read, and by extension difficult to navigate for reference’s sake,’ Marcia said. ‘I was inspired by Ruby Lavin’s work on Wanderhome, and figured that filtering the 1974 book through such a radically different format would force readers to read what it really says (since, originally, I did not rewrite any of the text except to make it better fit the page).’

Marcia eventually rewrote and reorganized the content to make Fantastic Medieval Campaigns a more user-friendly reference document than the OD&D booklets provide. At the same time, her voice in the text makes it very reflexive, reminding the reader that this is a self-conscious remaking and not an identical reproduction.

‘Although I am rewording the original text in FMC, I inserted myself at some points to remind the reader that I too am a reader,’ Marcia said. ‘It’s almost to lay down a fence between myself as the voice of the (rewritten) text and the text itself.’

The book is split into six sections: Mortals & Magic (character creation and core rules), Monsters & Treasure (exactly what it sounds like), Fantastic Adventures (dungeons, overworld adventuring, kingdom building, and variant combat), Chain of Command (the Chainmail ruleset), Optional Rules (some almost as old as D&D itself and some written this decade), and a glossary and appendix. Each major segment is color coded for ease of use.

‘It was important to me that it offered strong infrastructure as a sort of reference document (with indices, a glossary, and other tidbits),’ Marcia said. ‘So maybe it’s for people who want that, and I’ve certainly used it that way as well—when I play or write about OD&D, I use FMC as my shortcut.

‘At the same time, I think there’s a deeper level to the text as a text. Again, it’s certainly useful as a reference for OD&D, but it’s been formatted and re-presented in a way I think that allows it to serve as a commentary or critique of OD&D. The writing and presentation provoke the reader to re-evaluate OD&D or their understanding of it.’

Besides being a rogue editor, Marcia is also a scholar of classical literature. (The dedication page’s epigraph, “My soul yearns to speak of forms changed into new bodies,” is from Ovid’s The Metamorphosis, apropos on multiple levels.) The keen eye, critical attitude, and curatorial sensibility she honed in classics played an important role in Fantastic Medieval Campaigns’ conception and development.

‘My favorite part was searching for ambiguous points in the original text and sneakily replicating them without copying the words exactly,’ Marcia said. ‘The most egregious case, I feel like, was the description of robots, golems, and androids on a page listing additional possible monsters you might want to include in your campaign: “Self-explanatory monsters which are totally subjective as far as characteristics are concerned.” I thought that was quite arrogant! But if I were to expand upon these monsters, that would rid the reader of experiencing the same what-the-fuck moment I did. What I did was use very similar wording to describe the “% in Lair” column, itself being extremely unclear at first glance, and then describe the monsters as “You know what the fuck they are!”

‘This is a testament to FMC as a clone: there was so much ridiculous jank that I would have changed if I did not also want the reader to deal with it themselves (although I think I did sort of compromise by putting some of those changes in the Optional Rules appendix). The combat matrix is completely bizarre. The hit dice values are all over the place. The barbican has two prices listed on the castle construction diagram. Again, though, this was an experience I wanted to share with the reader, so I was very happy to replicate these weird inconsistencies and errors. Especially because when reading OD&D itself, people often gloss over them. It’s like people look at the pages and pretend that it says the same things as B/X. People will happily misremember what it was like.’

The year is 2000. You hold in your hands three large, glossy hardback books titled Dungeons & Dragons. Despite the abridged nomenclature, these volumes encompass a ruleset vastly larger than, and distinct from those original three booklets. Maybe you think this is a good thing; a consistent, comprehensive system means uniformity across the game. Maybe it pisses you off; a consistent, comprehensive system prohibits the versatility and creative latitude that instigated the game’s breakout success a quarter century ago. And if the latter’s the case, then maybe you’re about to embark on a crusade to resurrect old school–style play.

As one might expect of someone who rewrote OD&D from the ground up, Marcia is also a critical historian of the OSR, of which FMC is something of a capstone. Her blog post “The OSR Should Die” deftly contextualizes and periodizes the movement from its origins to the present day.

The OSR emerged as a reaction against D&D’s third edition, which made sweeping changes to the mechanics (pursuant to the totalizing project that began in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons’ first edition). It also represented a corporatization of the game; Wizards of the Coast had acquired the intellectual property from the defunct TSR in 1997, and Wizards itself had subsequently been acquired by multinational conglomerate Hasbro in 1999.

The initial OSR movement cleaved to a DIY hobbyist ethic and a less-systematized playstyle that embraced GM autonomy and player creativity (rather than, say, interfacing with the game strictly through the numbers on a character sheet). Third edition was the enemy, but it also supplied a solution: the Open Gaming License that gave designers carte blanche to make and publish materials for OD&D and AD&D, even to revive, revise, and republish older systems that would otherwise be lost to history.

If the OSR’s goal was to bring old-school gaming back into modern circulation, its triumph culminated, ironically, in D&D’s fifth edition . Co-designer Mike Mearls wanted to incorporate old-school sensibilities, and recruited the likes of self-styled OSR champion Zak S. as a consultant (though his credit was subsequently removed from the Player’s Handbook following multiple accusations of sexual abuse). The new edition was published in 2014, and in the adjacent years, Wizards entered the OSR market directly by reprinting limited runs of AD&D’s first and second editions.

Everything old was new again. The OSR had gotten exactly what it wanted. The problem, however, was that it was bullshit. The OSR was never about the old school, because the old school never actually existed as the coherent whole touted by the OSR. The OSR, as a trend, parallels the neoclassical movement in art and architecture, which rejected the popular Rococo style in favor of selectively drawing on classical aesthetics in service to the contemporary tastes. The OSR established its own play culture and goals, which it legitimized by declaring a project of reclaiming a long-lost golden age of gaming.

Of course, like all golden ages, that was a myth; there was no pre-existing uniform culture to resuscitate, and the OSR was merely one of many successors, not the hereditary heir of an unbroken lineage. Its alleged ethos is a hollow one, and today, we inherit it as a fragmented body of knowledge boiled down to little more than a marketing buzzword that designers either align with or define themselves in opposition to.

Nonetheless, the OSR objectively (if not coherently) exists, and Fantastic Medieval Campaigns is a retroclone that certainly falls into the category as popularly deployed. However, FMC exists not to contribute to the OSR’s identity but to challenge widespread assumptions and to critique the OSR’s foundation myth and popular image.

‘The OSR is not really about old books,’ Marcia said. ‘The OSR is a modern, revisionist interpretation of those old books. My hope with FMC was that it would illuminate ways in which, at least, the original D&D “deviates” from ostensibly old-school expectations. It’s not an escape room of the mind, and it’s barely a game of resource attrition. It’s a button-mashing hack-and-slash skirmish war game, almost a shadow of what legacy the OSR ascribes to Gygaxian D&D. To be clear, it is not that all TSR-era D&D has this in common, but rather that there is no singular D&D prior to Third Edition’s apparent intrusion. That is the myth on which the OSR is based.’

The year is 2024. You hold in your hands a single volume titled Fantastic Medieval Campaigns. It is a faithful rendering of the hallowed text first published five decades ago. It emblematizes, in negative, the culture war of the past two and a half decades—and it testifies to RPGs’ and gamers’ persistent ideological myopia.

‘I wanted to confront the reader with the reality of the text,’ Marcia said, ‘challenge predominant interpretations that ascribe modern (“old-school”) ideas to it, and transform something that (we think) we know all about into something unfamiliar.’

Fantastic Medieval Campaigns revises our understanding of what the ‘old school’ was through direct exposure to OD&D rather than filtering it through assumptions, interpretations, and faulty memories. The game’s reality is apparent in the text, but a true understanding of its origins come only through play, which itself challenges modern assumptions about the act itself.

‘I think the verb “play” here is back-porting some contemporary assumptions about how we interact with these texts, like this should be an out-of-the-box recipe for how to perform a certain game-ritual,’ Marcia said. ‘OD&D was not a lab experiment you can replicate. It was lightning in a bottle. It strikes the reader. It does not command. It inspires.’

But Fantastic Medieval Campaigns’ intellectual project extends beyond the game and its culture to the larger sociopolitical conditions that produced it. The finalized version of FMC debuted last year on 9 October—a carefully calculated date.

‘The United States acknowledges the second Monday in October as Christopher Columbus Day, the Italian explorer who sailed with a Spanish fleet in search of Asia and instead stumbled upon the New World,’ Marcia said.

‘He is celebrated as a pioneer of exploration, to whom we owe our lives today. He also is responsible for the genocide of 90% of the indigenous population in the century following his accidental discovery, besides his own “adventuring party” participating directly in the process. It’s difficult to read D&D and not make the connection between the adventurers’ exploits and the historical colonization of the Americas. Yet, like Christopher Columbus Day, readers shy away from this connection as well as the very implications of the adventurers’ fantasy campaign.

‘I think people try to absolve themselves of a “problematic” dimension to D&D by sanitizing the game’s content and finding ways to make the protagonists more heroic or moral in their view. The truth is that D&D is about violent colonialism in its very structure. D&D is about bringing the light of civilization to the darkest corners of a fantasy world, both literal or otherwise. It’s about a constant stream of treasure to extract and enemies to defeat. What does that sound like?’

The final page of Fantastic Medieval Campaigns bears the words “This Page Intentionally Left Blank”, centered and bold, but around it, printed faintly, almost like a palimpsest, is Fantastic Medieval Campaigns’ most direct and explicit critique of OD&D, from its inception through the present, as a playground for colonialist power fantasies based in white, male, heteronormative identity. Biases that are, unfortunately, still aggressively present in the hobby at large and particularly in a swath of the OSR.

‘There are two levels of exegesis that FMC attempts,’ Marcia explained. ‘The first is an exegesis of the game system as such, trying to reveal the gaps and ambiguities which readers have to resolve in order to play. The second is an exegesis of the text and implied setting of the game, which is not just the static fictional world but the social relations modeled inside it. The “blank page” connects the former to the latter, and completes FMC.’

But Fantastic Medieval Campaigns’ critique does not end there. Its additional economic commentary, however, is subtle and easily overlooked. In fact, it comes via a paratext rarely interrogated for meaning: the price tag.

You can download FMC for free via the Traverse Fantasy itch.io page—not pay what you want, but completely free. You can also buy the book in four physical formats—color and black and white, softcover and hardcover—on Lulu for only the cost of materials, printing, and shipping. The entire text (and many of the illustrations) are licensed under the Creative Commons.

This accessibility and openness harkens back, once again, to the prehistory of OD&D: wargamers and SFF fans were collaborative communities with little concern for intellectual property rights or for profit. (In The Elusive Shift Peterson writes, ‘the possibility that someone would pay money for the sort of half-baked ideas that filled these fanzines would have struck most as laughable.’) As OD&D gained traction, DMs circulated their house rules and creations via zines and periodicals. Decades later, the OSR did the same via Google+ and Blogger.

The commodity culture of today—which is dominated by crowdfunding on Kickstarter and selling on platforms like DriveThruRPG, itch.io, Dungeon Masters Guild, and various print-on-demand services—would have been alien to previous generations who identified as hobbyists. Today, however, creators overwhelmingly identify as publishers replete with digital storefronts and brand identities like Verbing Noun Press.

‘My strategy for FMC was to release it in such a way that directly challenges this norm,’ Marcia said. ‘It is quite unusual in our social context where game-books are primarily commercial projects and there is little DIY culture outside the scope of (ironically) modern, name-brand D&D.’

Ironic indeed given Papa Gygax’s changing attitude to the nature of play. During the OD&D era, Gygax stated his resistance to standardization, celebrated the game’s plurality, and characterized strict adherence to the rules as a fail state. But by the time of AD&D’s advent in 1978, he espoused the new edition (in The Dragon issue 43, also quoted by Peterson) as ‘a structured and complete game system aimed at uniformity of play world-wide. Either you play AD&D, or you play something else!’ Regardless of Gygax’s desire to have his cake and eat it too, and the persistence of systematization, modern players have other ideas.

‘5e is a culture rather than a system per se. Its enthusiasts are some of the few to recognize that they control their hobby, not the other way around. By extension, they don’t need to adhere to a system—rather, the system works for them,’ Marcia says. ‘The only unfortunate thing about this is that its creative commons is fenced by a firm that skims off the top. 5e players know that they don’t need another system, unlike what many indie enthusiasts (motivated by the same market forces as Gygax!) would like to think. However, they should also know that they don’t need Wizards of the Coast either.’

Can FMC fix the myriad problems it raises and change the culture? No. Of course not. But that’s not its purpose. It doesn’t offer solutions; it simply tries to expose the issues as they exist by showing us, firsthand, those problems’ deep roots and persistence from the very beginning. Like OD&D, Fantastic Medieval Campaigns is ambiguous and ambivalent in the right places; it is neither purely laudatory nor invective; it is a toolkit, and what we make of it speaks volumes about not only the nature of the game but of ourselves, and our desires for and assumptions about both.

Fantastic Medieval Campaigns is out now from traversefantasy.carrd.co

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 6 (August '24)