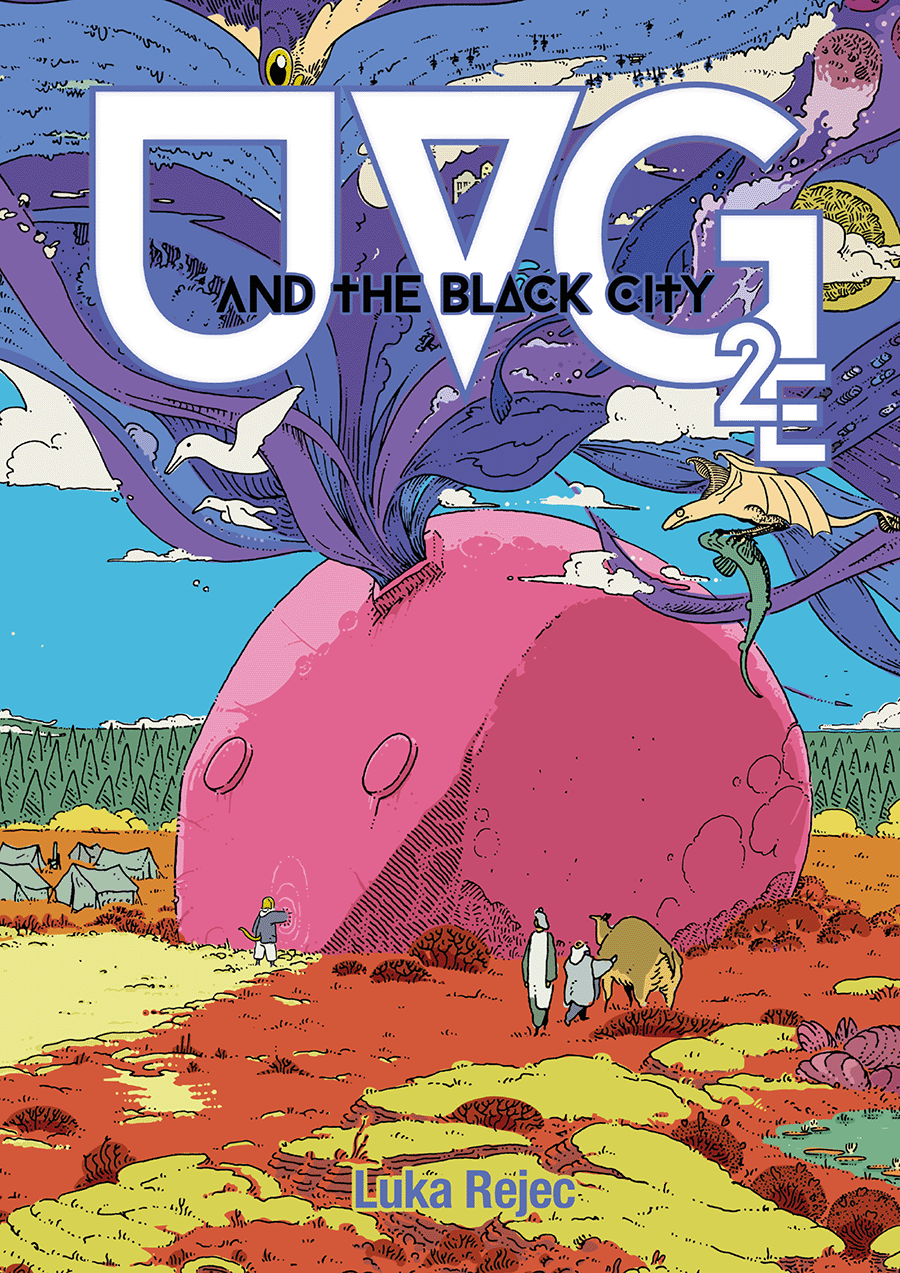

Ultraviolet Grasslands and The Black City has been floating around in a few formats for a while. But now for the first time with this new edition, it really feels like a game.

Older editions of UVG were a curiosity. Not only because of the game’s weirdness, its psychedelic Oregon Trail setting or its curious little mechanics – like the dedicated carousing system. No. Instead, what makes it curious is the way the text was a coy conversation with itself. The author, the well loved OSR writer and artist Luka Rejec, seemed to be hell bent on smuggling the game’s system away from readers of the book.

In the previous softback version it’s suggested that you should adapt the adventure to a system of your choice but, if you really must, you could use the included ‘SEACAT’ D20-style rules. These rules would later be presented on page 126 in something like an art-house essay on how to elide the actual moving parts of a game. Additionally, there was a philosophical explanation of the mind, body and soul which was somewhat intended to indicate which stats are tied to what. In short, I loved it.

And it was fascinating to read, a true and genuine oddity. Even if it wasn’t particularly helpful during play. I recommended it to every game designer I met and the setting to every GM who was as interested in ideas as they were how many goblins are in the cupboard. It’s clever and inventive, but it took quite a lot of patience to actually play it with immediacy and confidence.

The second edition though has fixed all this. Gone are the hidden rules. Now it’s a single page to get your game up and running, and it’s one of the first sections of the book. The overt philosophy of the game now lives inside the useful glossary. The inner cover now contains a beautiful – and possibly daunting at first glance – game flow diagram. But you’ll never be lost in the grasslands again for reasons other than your own poor planning and choices.

Plan you must. Or, alternatively, perish. Procedure is at the heart of UVG 2E. This is a fantastical Oregon Trail after all, and while you might not die of dysentery as you may in the classic video game of settlers’ struggles in crossing the final part of the uncolonised and pre-United States, you’re still going to run into random and cruel misfortunes as you travel. You might have sat on a cactus, accidentally picked some totally poisonous flowers by mistake, or just be a bit under the weather.

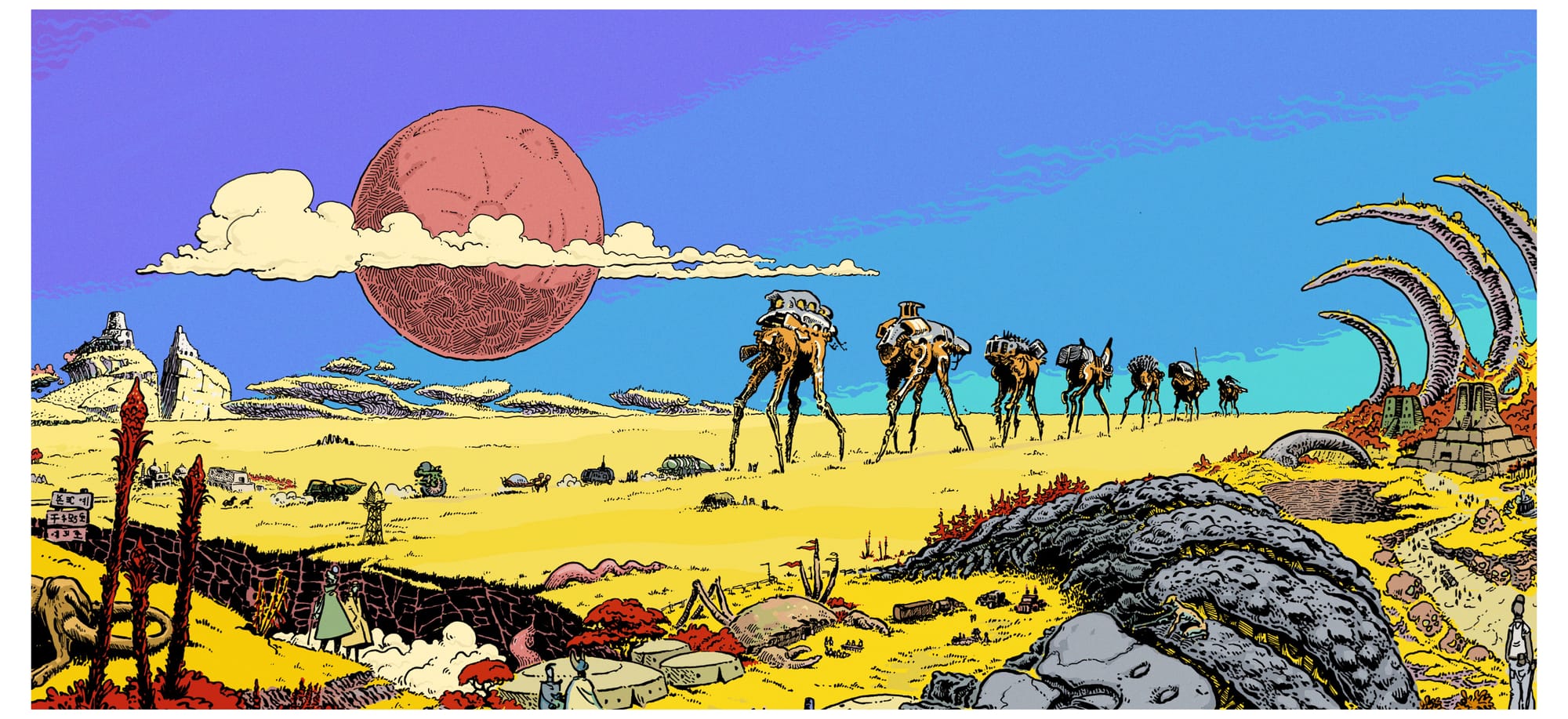

Weather itself is a big feature as you travel between sections of the huge trail. You’ll always be told when the sun rises, and whether you can see anything through the refracting light. It’s a detail that plays into the procedure of the book, given some of these mostly mundane snippets fit within a game which is partly about caravan management. Much of the game is spent scribbling on the long map, which we recommend you print out and spend some time sellotaping together. It’s a beautifully stark purple on white rendition of the trail you’re following, each point giving you options for further exploration. Players become obsessed with the choices they’re making because often, should they want to ‘advance’, they’re leaving behind the chance to visit somewhere else.

UVG is a game of tourism and hardship. Beautiful places filled with biomechanical menaces, ancient and lost behemoths, cat lords, poly-bodied entities and porcelain masks beckon you within the Moebius-like artwork created by Rejec. It’s a game of vast petrol-spill vistas, of creeping through the bones of ancient beasts or stumbling across the occasional sad and hopeless immortal or ghost community which possesses the local tribe in a kind of time-share-body deal.

The characters you meet are painted quickly, usually with an attitude and something they know. The places are fantastical, and players accrue experience simply by visiting them. The game is a series of postcards in this way (and even includes some in the back). Discoveries are made at each location which can allow the players to find more depth in side-quests that, in truth, could have been their own settings entirely and will often give players the chance to pick up some extra, much needed, loot.

See, UVG is not a dungeon crawl or a traditional game of quests. Don’t expect to be slowly wading through piles of goblins in search of treasure. It’s all much more zoomed out than that. Everything is played, more or less, in summary. Except for those moments where a fight does break out or a chase occurs. Even then, this isn’t a game of complex combat mechanics.

Much of the creatures and peoples of the game aren’t inherently hostile – things getting violent is almost entirely down to players’ greed or need to poke everything with the sharp end of whatever they’re holding. Equally, players who want to dig into everything will find themselves running out of time and soon learn that it’s best to enjoy the view and pick their moments to extract value from their trip.

Refereeing the game is a surprisingly intimate experience for all of this. It has the feel of ‘running’ a Choose Your Own Adventure book with someone. It’s less about knowing what’s coming up as the referee, but instead discovering what the players want to find as they explore. You’re a guide in that sense rather than the player who sets off all the traps. You certainly can do that too, but the game doesn’t demand it. Much of the hard work and joy of the game comes from trying not to engineer too much. Your players are often trying to survive, and finding a few sackfuls of rare materials which will let them get into trouble in the next town is more than enough motivation.

You might imagine players want to explore this gorgeous world because of the gorgeous book in front of you. But that’s not it, they’re scrabbling around looking for their next meal or meal ticket. Your players are a bunch of Han Solos, not Luke Skywalkers. That guy wouldn’t last long here at all.

There’s a question of whether I like UVG in its original form because of its weird self-referential conversation and playful language. The latter is still there, but I think knowing this game actually wants to be run means the second edition is the version you’ll want to own. All in all this is a better game and worth a pilgrimage.

In fact it might just be the trip of a lifetime.

Writing & Art: Luka Rejec

Published by: Exalted Funeral

This feature originally appeared in Wyrd Science Vol.1, Issue 5 (Dec '23)